Lessons from Europe (don’t knock down ancient buildings)

Italy, Greece and many other countries on continental Europe (especially Prague) preserve their ancient buildings, if they are safe and in good order. Instead, planners in England are always knocking down ancient buildings, in order to build ugly monstrosities in their place.

There are much tougher laws in Italy, overseen by the Ministry of Culture, that has to review any plans and issue permits, and will block any building works that harm heritage. They will also set fines, even if a developer knocks a hole in a listed wall.

In Italy, you would never have had HS2 destroying England’s second-oldest pear tree (Warwickshire), it simply would never have been allowed to happen – trees or buildings.

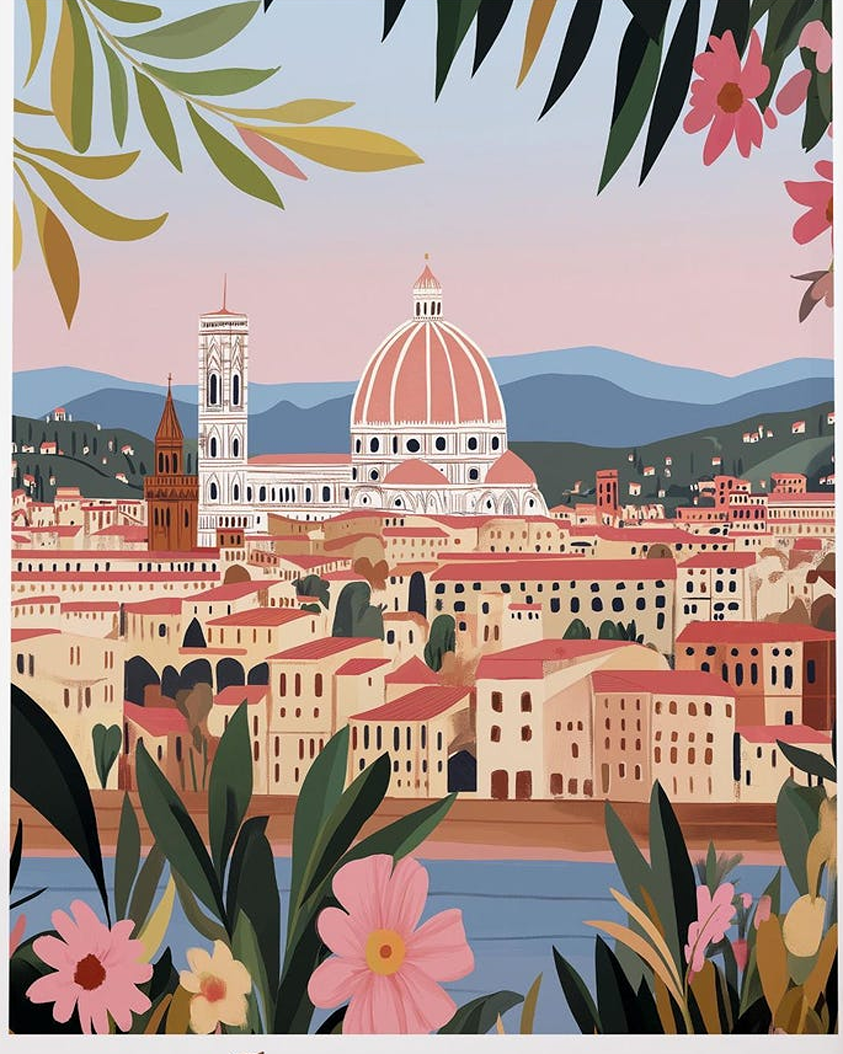

In Florence, the Renaissance core is a conservation area. New builds face tight rules on height, colour, and materials. Shopfronts cannot add large neon signs. Even window frames must match approved styles. The result feels authentic because it is built on evidence and care.

In Venice, rules protect the skyline and the waterways. Large ships no longer pass close to St Mark’s Square. Repairs to canals must use approved methods and materials that respect the city’s fragile foundations. The focus is not just on pretty views. It is about keeping the city safe from erosion, vibration, and water damage.

In Rome, strict zoning guards the historic centre. Planners cap building heights and protect key sight lines, for example the view of the Victor Emmanuel II Monument along Via del Corso. Timed entries at the Colosseum spread footfall, cut wear, and improve the visit. Recent repairs cleaned stone, fixed drainage, and stabilised the arena’s walls without hiding the marks of time.

In Milan, stone cleaning on the Cathedral uses gentle methods, like laser cleaning, to remove grime without damaging marble detail. In Assisi, seismic retrofits after the 1997 earthquake strengthened the Basilica of Saint Francis. Engineers added steel ties and discreet supports, then conservators restored frescoes with pigments that match the originals.

Balancing Tourism with Protection

Florence (one of the world’s most beautiful cities) is trying to prevent over-tourism, due to littering and pickpockets. One official noted ‘No museum visit – just a photo then they take the bus to Venice – we don’t want tourists like that’.

Nearby is Pisa, whose ‘leaning tower’ recently had to be adjusted to keep it leaning, instead of falling down.

We have our own ‘crooked tower’ in Chesterfield (Derbyshire) with a church whose spire tilts at a certain angle. There are legends as to why (one is that the devil sneezed so badly, that is caused the spire to warp!) It’s more likely due to wind and engineering.

Greeks Don’t Knock Down Ancient Buildings

In Greece, ancient buildings are loved and preserved. Not bulldozed to make way for skyscrapers. Old buildings are also home to roosting bats and barn owls. Replacing old facades with glass also contributes to bird strike. Read how to help stop birds flying into windows.

Greece treats antiquities as part of public life, not as fenced-off relics. The goal is to protect, restore, and integrate. You see it on every hill and in every town square.

Strict Laws That Safeguard Greece’s Past

The Hellenic Ministry of Culture is the gatekeeper. Law 3028/2002 protects antiquities and cultural heritage and defines how they must be treated. Monuments from ancient times are protected by default. Newer buildings can also be listed as protected monuments, often based on age, design, or cultural value.

Many structures older than 100 years fall into this bracket once listed. Demolition is then off the table without formal approval.

Lessons from England’s Lost Buildings

The UK has many success stories in conservation, yet high-profile losses keep coming. These cases show how short-term thinking can erase shared memory.

Birmingham Central Library: A Modern Loss

Opened in the 1970s, the library stood as a bold example of Brutalist design. It offered large reading rooms, a famous central hall, and a strong civic presence. Critics called it ugly. Fans called it brave. When the decision came, campaigns for listing failed. The wrecking crews moved in.

What did the city lose? A public space with a clear identity. A building that captured a moment in social history. A chance to adapt a complex into new cultural uses. Now, the memory is held in photos and angry op-eds.

Euston Station’s Doric Arch was taken down in the 1960s. Part of a grand entrance, it fell to modernisation. Historians still call it a national mistake. The arch became a cautionary tale for planners and ministers alike.

Blackpool lost its Art Deco baths in the late twentieth century. The complex hosted major galas and water shows, and it was linked with star swimmers, including appearances tied to Johnny Weissmuller. Demolition removed a civic stage, not just a pool. The replacement did not carry the same civic memory.

Johnny swam the entire length of the Derby Baths underwater, and was such a strong swimmer that he once saved 11 people from drowning after a boat accident, while training for the Chicago marathon. He and his brother repeatedly dived in the water, to save as many people as possible. Then two days later, he won the marathon.