Roald Dahl (a life as dramatic as his stories)

Roald Dahl stands out is still (years after his death) one of England’s most popular children’s writers, although many were dark and strange (he also wrote a lot of the adult stories for TV’s Tales of the Unexpected).

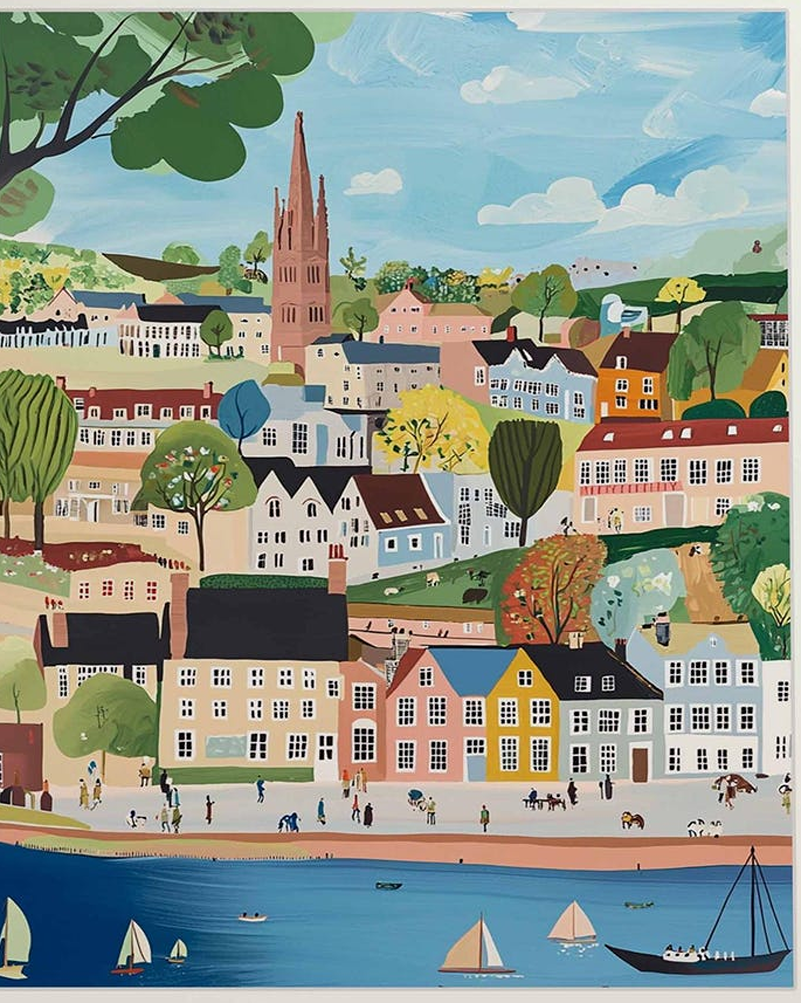

Born in 1916 in the Welsh seaside town of Llandaff, his parents were successful Norwegians (he spoke the language, attended a Norwegian church and at 6ft 5in tall, was a big friendly giant himself!

Growing up surrounded by stories of Norse mythology and the old country (he was named after the explorer Roald Amundsen who disappeared on an Arctic expedition), he and his mother travelled to the Lake District, so he as a child could write his heroine Beatrix Potter.

It wasn’t long before (after serving in the Royal Air Force) he was writing children’s stories himself. Always in his garden shed, with HB pencils on yellow paper!

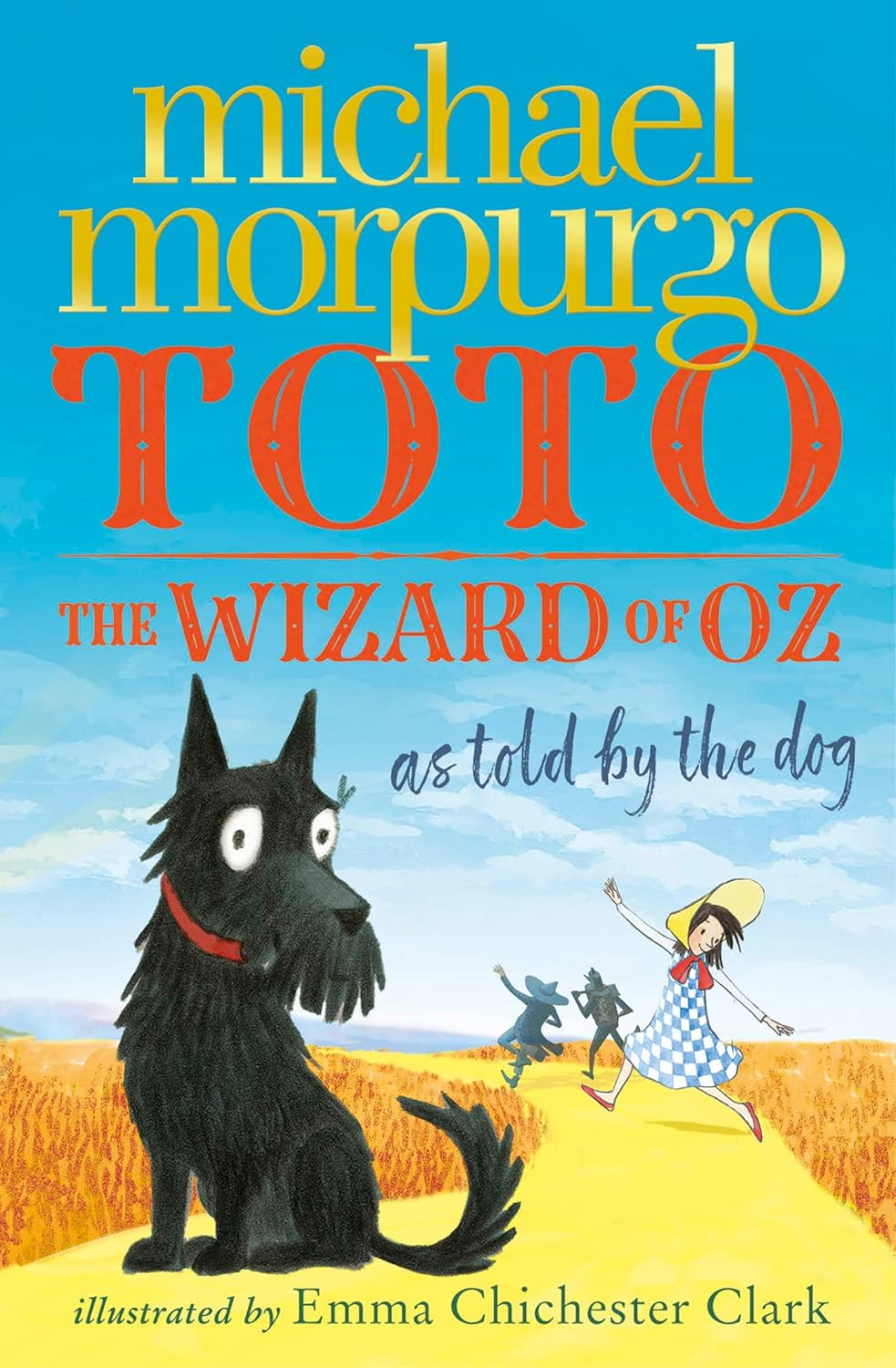

I understand what you’re saying, and your comments are valuable. But I’m gonna ignore your advice. Fantastic Mr Fox

If a person has ugly thoughts, it begins to show on the face. And when that person has ugly thoughts every day, every week, every year – the face gets uglier and uglier, until you can hardly bear to look at it. Mr Twits

School Experiences That Shaped His Storytelling

Roald attended a strict boarding school with harsh punishments. And it’s believed these school memories which never left him, influenced many of his stories: authoritarian headmasters, the smell of boiled cabbage and the shock of unfairness were all common themes.

As a child, being one of the cadets sent to test new chocolate bars at Cadbury, of course became the inspiration for one of his most popular books: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Roald did not like the film version in 1971.

Just like old fairy-tales, this one had a moral tale: of the several sins. Each child has one (gluttony, pride, greed, wrath, sloth) – all meet a sticky end, usually involving chocolate.

Roald also invented his own language of gobblefunk!

But he also had a serious side. Not just writing the film script for Chitty Chitty Chitty Bang (for his friend Ian Fleming), he also wrote the script for the James Bond film You Only Live Twice.

Ian’s brother was married to Celia Johnson, who played the lead role in Noel Coward’s beautiful romantic tearjerker Brief Encounter.

A Very Dramatic (and tragic) Private Life

Roald’s wife was American actress Patricia Neal (above, who played the boy’s mother in the 50s sci-film The Day The World Stood Still).

In 1960, their baby was badly injured when struck by a New York taxi. Roald helped to develop a device that helped the medical condition caused by the accident, which is still used today, having helped thousands of children.

Two years later, their young daughter died of measles. After these two tragedies, he visited the former Archbishop of Canterbury, who was told that although his daughter was in heaven, her beloved dog Rowley would never join her. Roald then lost faith in religion, writing:

I wanted to ask him how he could be so sure. I sat there wondering if this great and famous churchman really knew what he was talking about, and whether he knew anything at all about God or heaven. And if he didn’t, then who in the world did?

As if that was not enough tragedy, in 1965 his wife (while pregnant with their fifth child) suffered three burst cerebral aneurysms, fell into a coma for weeks, and had to learn to walk and talk again.