The wind on the Yorkshire moors feels like a character in its own right, fierce and honest, much like the three sisters who grew up within its reach. Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë turned quiet rooms and rough paths into scenes of passion, defiance, and moral courage. They wrote as Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, names chosen to hide their gender in a world that often closed doors to women.

Their lives were short, their circumstances hard, and their world small. Yet their books still fill shelves and ignite debate. Why do these stories endure? Because the Brontës wrote about desire and duty, cruelty and care, freedom and faith, all set against the moorland’s raw beauty.

The Early Lives of the Brontë Siblings

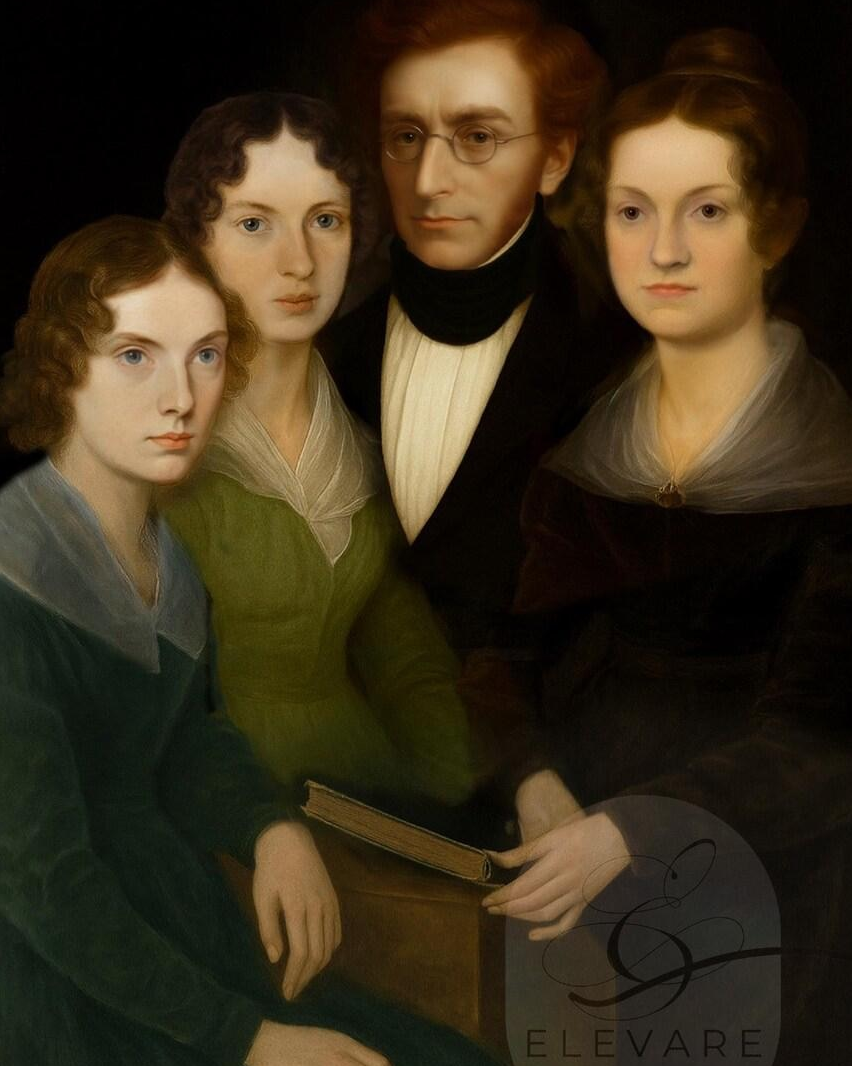

The Brontë children grew up in Haworth, a hill village where the church yard crowded near the parsonage. Their father, Patrick Brontë, was an Irish-born clergyman with strong views and a love of books. Their mother, Maria, died in 1821, leaving six children behind. Two daughters, Maria and Elizabeth, died young after time at a harsh boarding school. Loss marked the family early, and silence often fell over the house.

The parsonage stood close to the moors, and the sisters walked those paths in all weathers. Their brother, Branwell, shared their early play and their appetite for stories. Together, they built vast imaginary kingdoms with complex maps, laws, and loyalties. Charlotte and Branwell tended Angria, a world of intrigue and rivalry. Emily and Anne shaped Gondal, a land of storms, rebellions, and fierce queens. These worlds trained their minds in plot, voice, and character.

After their aunt, Elizabeth Branwell, moved in to help raise them, the girls learned at home, with brief spells at school. Books and magazines fed their ideas. When they tried to publish, they chose neutral names, Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, to shield their work from bias. The moors gave them a stage, the parsonage lent quiet, and their losses sharpened their will to write.

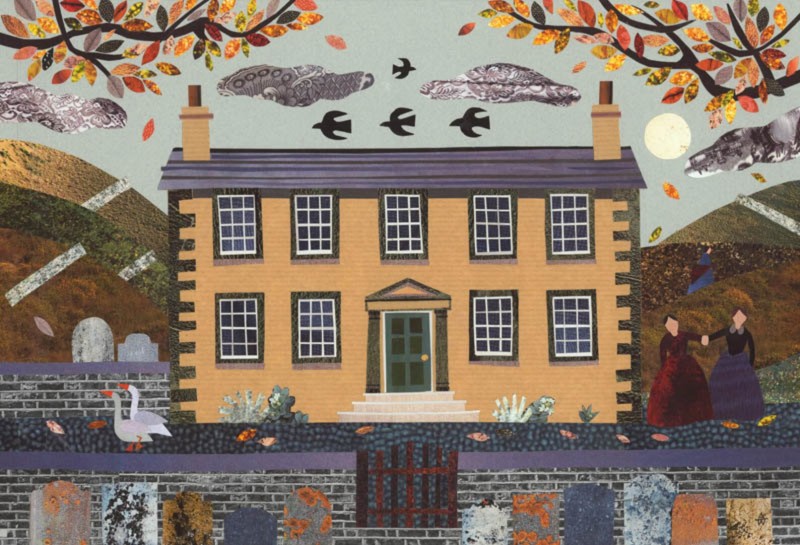

The Yorkshire Village of Haworth

The Yorkshire village of Haworth has now obviously become a tourist mecca, for literary fans of this family. The former family home is now a museum.

It’s a pretty place but like anywhere (Grasmere in Cumbria – home to Wordsworth), the local council and tourist board are making it a bit gimmicky, to bring in income. You can go ‘where Heathcliff and Cathy’ embraced, and you are said to be married within a year. Oh, please!

Why not just protect it as a pretty village, and stop so much over-tourism? Which likely brings in too many people and too much traffic for local people. And likely sends the cost of buying a home there out of budget too.

In the 1960s, this Pennine village was still a working town (just 10 miles from Bradford). Now most of the indie shops have gone (the baker, the newsagent) to replaced by souvenir shops and most of the buildings are holiday-lets for foreign tourists.

One wonders what the four siblings would have made of all this. After all, they lived in a parsonage and were the children of the local minister.

Childhood Tragedies and Creative Beginnings

Their mother’s death in 1821 left a gap that never closed. Later, after a typhoid outbreak and grim conditions at Cowan Bridge School, the sisters came home, worn and changed. They turned inward and towards each other, building a strong bond through reading and play.

They wrote tiny books in minute script, filled with tales of soldiers, princes, and daring schemes. Stories like The Young Men’s Magazine, The Foundling, and The Green Dwarf show early signs of wit, structure, and drama. Grief did not silence them. It pushed their imaginations into motion.

Education and Influences on Their Writing

Cowan Bridge School left deep marks. Its cold food and strict rules shaped Charlotte’s picture of Lowood in Jane Eyre. Much of their real education came from self-directed reading at home. They read the Bible, history, travel, and periodicals like Blackwood’s Magazine, which prized sharp style and bold thought.

The moors outside offered a different kind of schooling. That stark horizon carried weather like a mood, and it enters their pages as symbol and spur. The Romantic poets taught them to write about nature and feeling with urgency, while their own lives demanded honesty about class, work, and the limits placed on women.

Famous Works in Brontë Literature

The Brontë sisters broke into print first with Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. Sales were poor, yet the poems show strength in rhythm and voice. Publishers doubted their novels too. Rejection letters piled up before acceptance came, and even then, critics speculated about the Bells’ identities. The pseudonyms helped them reach the press and helped readers take them as serious artists.

Common threads run through their books:

- Female independence: heroines seeking work, voice, and moral ground.

- Class and power: wealth, rank, and their tight grip on choice.

- Love and cruelty: deep feeling beside neglect, violence, and revenge.

- Nature and the uncanny: storms, ghosts, and houses brimming with memory.

These themes sit within vivid scenes of governess life, grim schools, cruel masters, and raw moorland weather. Each sister shaped the shared concerns in her own way.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre: A Story of Strength

Jane Eyre follows an orphan who refuses to bow to injustice. Jane endures Lowood’s hardship, grows into a governess at Thornfield, and falls in love with Mr Rochester. The novel puts her moral compass at the centre. When faced with a secret that makes her future with Rochester impossible, Jane chooses dignity and self-respect.

Lowood reflects Charlotte’s bitter memories of school. Yet the book is not a simple record. It fuses romance with moral struggle and social critique. It was an instant success, praised for its strong voice and lively scenes. Readers cheered a heroine who says no when it matters, and yes on her own terms.

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights: Wild Passion and Darkness

Wuthering Heights (covered in a song by Kate Bush) has a double structure and a brooding mood. Heathcliff and Catherine love with a pride that bends towards ruin. The moors act like a mirror to their rage and longing. Houses, Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange, stand as symbols of storm and calm, harshness and polish.

The novel blends Gothic elements, unreliable narration, and cycles of revenge. Early reviews were puzzled, some even hostile. Its cruelty and intensity shocked Victorian taste. Over time, critics saw its power and shape, and now it sits as a classic. The book probes how class, orphanhood, and abuse shape character, then lets nature’s vastness swallow civil niceties.

Anne Brontë’s Realistic Portraits of Society

Agnes Grey gives a clear look at governess life. Agnes faces spoiled children, petty employers, and the thin line between genteel poverty and dignity. The prose is spare, the scenes exact, and the message plain. Work for women was fraught and often thankless.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall goes further. Helen leaves an abusive, alcoholic husband to protect her child. She supports herself by painting, guards her privacy, and tells her story with strict honesty. Anne faced harsh criticism for its subject, yet the book stands as one of the boldest Victorian portraits of marriage, addiction, and a woman’s right to refuse harm. Some overlook Anne, yet her realism and moral clarity feel modern and bracing.

The Lasting Legacy of the Brontë Siblings

The Brontës changed how readers see women on the page. Their heroines work, think, and choose. Their books question power held by money and men. Modern writers borrow their structures, voices, and storms of feeling. Film and TV keep returning to Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, each time finding new angles on class and desire.

Their personal story adds pathos. Branwell’s decline from addiction and failed hopes weighed on the household. Illness took Emily in 1848 and Anne in 1849, both still young. Charlotte married late, then died in 1855. The parsonage holds their shadows, now the Brontë Parsonage Museum, where visitors stand in the rooms where they wrote.

Their books cut against the grain of their time. They spoke about work, abuse, and equality, and they did so with energy and craft. The setting, the moors and the parsonage, helps fix their work in place, yet the questions they ask travel well. What is freedom worth? What will you risk for love or truth? That is why readers still turn the pages.

The Sad Early Deaths of the Brontë Siblings

All four siblings died tragically young, so it’s amazing that their literary works continue today. There were two other siblings too (Maria and Elizabeth, who both died as children from TB).

Patrick (Branwell) died age 31, also from TB and other complications.

Emily died age 30, just 4 months after her brother, again from TB complications, from catching a cold at her brother’s funeral.

Anne was just 29 when she died, and again had TB.

Charlotte died at 38, who lived with her blind and ill father. She did eventually marry, but died 9 months later (again from TB combined with extreme nausea from pregnancy, which led her not being able to eat or drink properly. She was just 3 weeks from her 39th birthday.