Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group

Virginia Woolf was one of England’s most celebrated writers. She spent a lot of time in Cornwall (a lighthouse here inspired a book) and London. But spent most of her days in later life in East Sussex, near Glynde (now a privately-owned village and near to one of England’s top opera houses).

In early 20th century London, Virginia, her sister Vanessa and some other friends began known as the Bloomsbury Group. They would gather to talk about life, truth and beauty, and new ways to think about society. They were quite unconventional for the time (Virginia did marry, but also had relationships with women) quite scandalous, back in the day!

Early Life and Sussex Influences

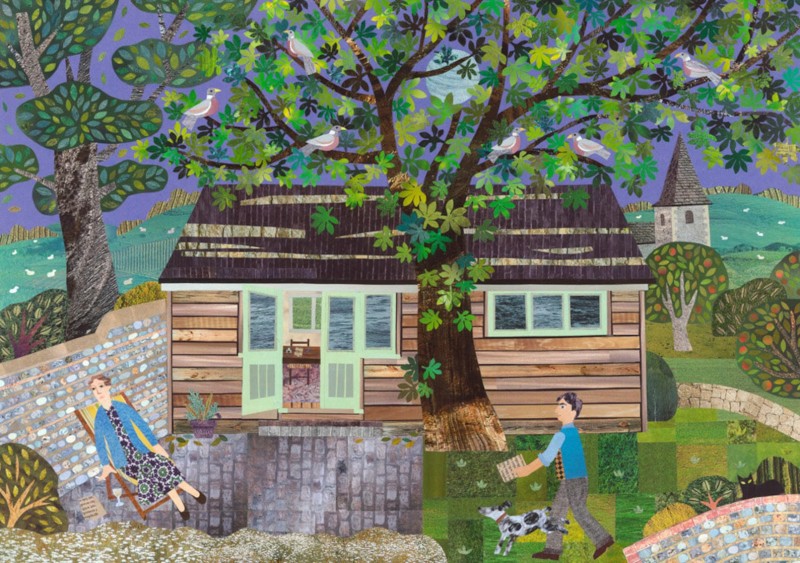

Born in 1882 to a family of ‘thinkers and writers’, her childhood summers were spent in St Ives. After her parents died, her refuge became Sussex, which she adored due to the rolling South Downs, shifting light and salty air. And villages with wild gardens, and a nearby changing coastline.

The Formation of the Bloomsbury Set

The Bloomsbury group however mostly met in London, in the quite houses in Gordon Square and Fitzroy Square. People would visit the book-heavy homes to have informal conversations amid bookish friends. The group became political during World War I, due to many members being pacifists.

Virginia Woolf’s Central Role

When Virginia arrived (through her sister), her curious nature and wit made her a popular member of the group, and after marrying Leonard Woolf, they founded Hogarth Press, which printed modern fiction, essays and translations.

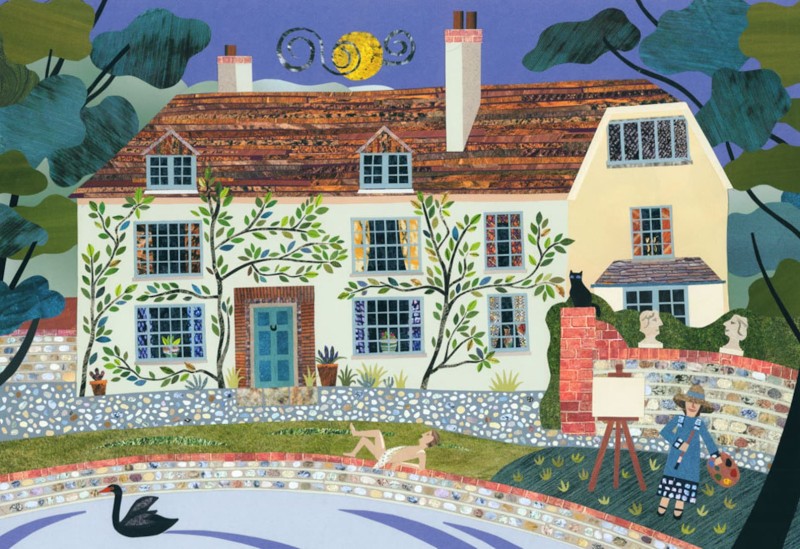

The group was also beneficial for Virginia, who struggled with her mental health. The walks and quiet rooms and work helped, often taking time to read drafts and give notes, during depressive spells. Throughout her life, Virginia remained close to her sister Vanessa Bell, and they lived near each other.

Lasting Legacy of The Bloomsbury Set

Although long gone, the Bloomsbury Group left a mark on literature, art and social thought. They supported peace and the importance of the arts. They even have shaped how colleges and universities teach literature and art.

Virginia’s old home is now situated in England’s newest protected National Park, something no doubt she would have been pleased about. She would often walk the South Down paths to inspire her writing.

Sadly it was also here that her depression continued. One day, she filled her overcoat pocket with stones, and walked into the River Ouse. She was just 59 years old.