Let’s Meet England’s Wonderful Wading Birds!

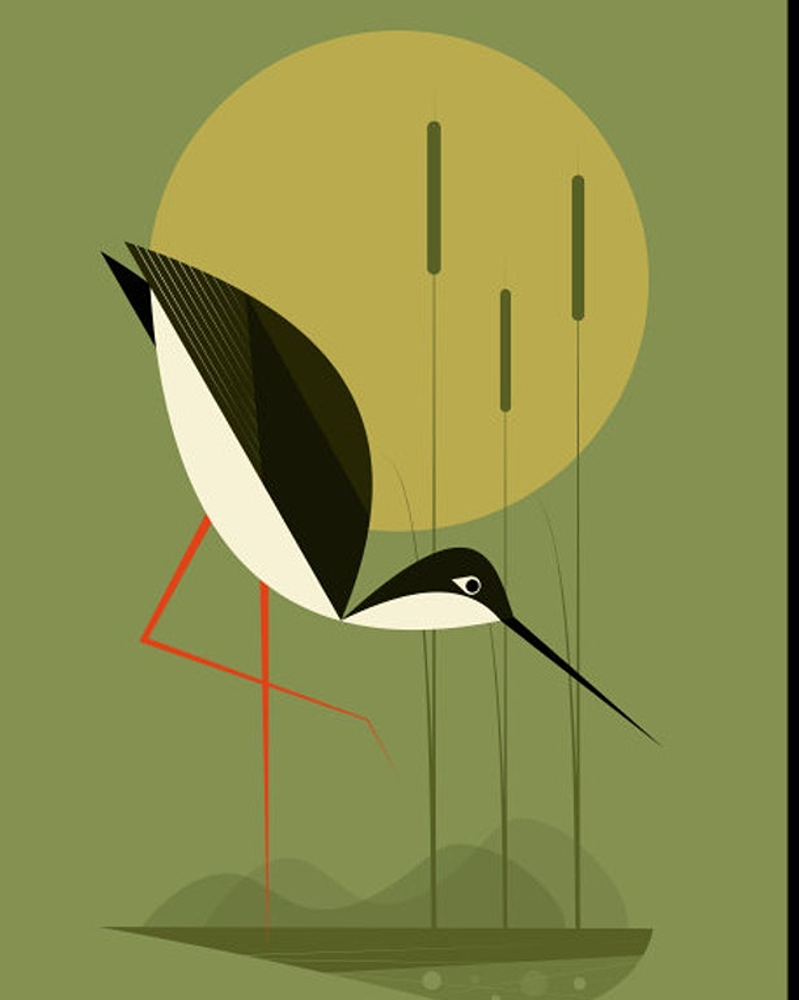

Avocets by Mr Watson Design

Wading birds (which sometimes live by the coast but mostly in wetlands) have long legs and long bills, to enable them to feed on worms, crustaceans and invertebrates in muddy estuaries. Some migrate here from the Arctic, others live in England year-round. All are at risk, due to lack of wetlands and modern farming methods, which off-run chemicals into water ways.

Also read about endangered curlews and herons, bitterns and egrets.

Often seen in huge flocks (often in tens of thousands), they are especially seen on Morecambe Bay (north west England) and The Wash in East Anglia.

Keep at least 50 metres away from wading birds (they need more space at high tide), as flying away wastes energy that could be used for feeding. Keep dogs away, as disturbing nests could cause birds to abandon chicks (most areas popular with wading birds have sinking mud, so are not safe areas to walk anyway. Read more on keeping dogs safe at the seaside.

Morecambe Bay and the Wash (wading bird heaven!)

Most of England’s wading birds live in wetlands and estuaries.

Morecambe Bay is the second largest bay in England that covers 300 square km of intertidal mudflats and sands, flowing from the River Lune in Lancashire. It’s a wetland paradise for over 200,000 wading birds. And also home to wildfowl, gulls and the rare brown fritillary butterflies.

One pretty town on Morecambe Bay is Cumbria’s Grange-Over-Sands. The ‘over-sands’ name is not just for show. Back in the 1800s, the local vicar got fed up of his letters ending up in Grange (Borrowdale) near Keswick. So he changed the name, to receive his post!)

The Wash (on the east coast where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire) is home to some of the best best saltmarshes and mudflats in England, fed by four rivers. Freiston’s sea wall has been adapted to increase saltmarshes to give more habitats for wading birds, and acts as natural flood prevention.

It’s also home to common seals (who give birth on sandbanks in summer, and important nursery areas for fish. Today the area is protected (one exploited shellfishery led to a decline in bird populations).

In 1216, King John took a safer route from King’s Lynn to Lincoln, but his men and horses died, when his baggage train with the crown jewels were lost in fast-moving tides, near what is now Sutton Bridge. The king became ill and died a week later, and the wagons were never found.

Let’s Meet Some of England’s Wading Birds!

Avocets use their unique beaks to build ground nests surrounded by water. Mostly found in southern and eastern England, they almost became extinct, but conservation efforts means numbers are returning. These black-and-white birds are the emblem for RSPB.

Black-winged stilts have long pink legs and black-and-white feathers. A rare breeder in England, these birds have started to nest here, due to warmer weather. They like shallow lagoons, where they wade through still water in search of insects, snails and small fish.

Black-tailed godwits are slender birds with orange-brown necks in spring, and black-and-white wings. Mostly migrating from Iceland, some breed in England’s Fens in eastern England. Bar-tailed godwits are smaller, with striped tails and upturned bills.

Common snipes use a ‘sewing machine’ method to investigate marshes for food. Jack snipes are only seen in England in winter (they pump their bodies up and down, as they walk!)

Dunlins (and little stints) look similar to curlews, with downward-curving bills, and although brown in breeding season, are grey in winter. These small busy birds rarely rest, dashing about in large flocks to probe the mud for food. In winter, the sight of thousands wheeling in the air is a true spectacle.

Knots have brick-red plumage, though look more grey in winter. They migrate from the Arctic each autumn, to feed on shellfish and marine worms.

Lapwings have striking black and white plumage and distinct calls. They are critically endangered (at risk of extinction in west England) due to lack of wetlands. They also like grasslands for food and camouflage against predators, laying eggs in shallow scrapes.

Redshanks have carrot-coloured legs, and make fast-piping whistle calls. They again arrive from northern Europe in winter (greenshanks and spotted redshanks have longer legs and bills).

Plovers are common on England’s coast (ringed plovers are larger, and little-ringed plovers have golden rings on their eyes). known for their stop-start running after prey.

Ruffs have impressive ruffs around their necks, and favour flooded meadows, wetlands and muddy edges of lakes. They rarely breed in England, but migrate here from abroad.

Snipes are secretive birds that hide in reeds or long grass. When startled, they explode from cover in a zigzag flight, and in spring, males ‘drum’ by vibrating their tail feathers in a proud display.

Spoonbills are named after their spatula-shaped bills, which can easily sift through water and mud to find tasty treats like beetles, small fish and tadpoles. Mostly found on the North Norfolk coast, abroad these endangered birds roam the icy coasts of Siberia to lush wetlands of Africa.

Common cranes are England’s tallest birds. Mostly found in Norfolk, Cambridgeshire and Somerset, they are known for their beautiful courtship dances (each bird walks around the other with spread wings, then leaps in the air to bow, and throws grass blades and sticks in the air, to show their love!)

How to Help England’s Wading Birds

Curlew by Mr Watson Designs

- Stick to Paths Near Potential Nests. Keep to official walking paths (especially during breeding season from April to July) and keep dogs on short leads. You can download free signs in English or Welsh.

- Avoid Buying Peat Compost. This protects wetlands, where wading birds live. Make your own compost or choose peat-free brands. Keep fresh compost away from pets (read more on pet-friendly gardens).

- Practice Nature-Friendly Farming. As well as protecting wetlands (avoid planting trees in these areas, as they can help to hide predators), leave areas with nesting birds alone. If you mow, start from the inside out to edges of fields, so creatures have a chance of escape.

- Campaign for Wildlife-Friendly Planning. Write to your MP. We need affordable homes, but not on land that is home to our native and endangered wildlife. Politicians can work with wildlife ecologists, to learn how to build without harming other creatures.

- Report Litter to Fix My Street. Councils (no matter who dropped it) are responsible for clearing it on public land. For private land, they can serve Litter Abatement Orders to have landowners clear it.

- To avoid wildfires, never smoke near farmlands or wetlands (and use a personal ashtray to immediately distinguish cigarettes.

- Anglers can use a Monomaster to store fishing gear, until deposited at a fishing line recycling station.

- You can report wildlife crime (anonymously) to Crimestoppers. In many cases, there are rewards (using a bank code, so no personal details are given).