The Lake District (England’s Largest National Park)

The Lake District is England’s largest National Park, situated in the north west county of Cumbria. It’s a popular walking holiday destination.

Always stick to the Countryside Code to help protect all creatures. If near to lakes or coastal areas (there are a few), read up on water safety for dogs.

England’s largest body of water is Lake Windermere (in the news these days due to issues with sewage pollution). The area has strong literary connections (William Wordsworth warned not to put a railway station at Windermere, for fears of over-tourism). He was right.

Ospreys were almost extinct a few years ago (due to hunting in Victorian times, at one point there was just one breeding pair left, in Scotland). These fish-eating birds of prey look like large brown and white gulls, and migrate over 3000 miles from West Africa, each year.

They use reversible toes (that turn 180 degrees) to hunt for slippery fish. They are such good ‘fishermen’ that around 70% of dives are successful. And if hungry, they usually catch a fish in around 12 minutes. Their eggs often hatch one-by-one, sometimes up to 5 days apart. The birds are possibly named after the Latin word ‘ossifragus’ (it means ‘bonebreaker).

Thanks to conservation efforts in England, the birds now have a bright future. They are still only really found on Rutland Water (a large manmade lake in the East Midlands – England’s smallest county). And in Cumbria’s Lake District.

Rewilding is a big thing in the Lake District, since the last golden eagle died on the remote eastern fells. Birds of prey are wild creatures, so should always be left alone, unless you know they are injured or in danger. Parents are usually nearby, so observe if concerned. Read more on how to help England’s birds of prey.

Visiting all 36 Islands of the Lake District

36 Islands is an adventure book with a difference, a poet who decides to visit all 36 islands in England’s largest National Park (some no more than rocks, others perfect for a night of wild camping).

Armed with just an inflatable canoe (and inspired by Inspired by Wainwright and Wordsworth), the author journeys beyond the tourists and busy roads, to islands both real and remembered.

You can feel the chill of waters creeping into your bones, as Twigger paddles his way to some of the most inaccessible spots. Shaun Bythell

He visits all the well-known lakes (and some not – who has heard of Devoke Water?) It’s usually raining, but he’s an irrepressible optimist. Fiona Reynolds

Robert Twigger is an award-winning poet, whose 12 books have been translated into over 20 languages. He has also crossed Canada in a homemade canoe, and was the first person to travel on foot across the Egyptian Great Sand Sea.

His previous book Walking the Great North Line saw him travel in a straight line from Stonehenge to Lindisfarne, to discover secrets of our ancient past.

Why Does it Rain So Much in the Lake District?

The Lake District (England’s largest National Park) is officially the wettest place in England. Here you can be soaked to the skin within minutes of a downpour. So be sure to bring your natural rubber wellies and windproof umbrella, when visiting!

So why is this area of northwest England rainier than everywhere else? It’s all to do with the nearby Atlantic Ocean, which carries large amounts of moisture from the wind. Mountains (all of England’s highest ones are here) force air to rise. This causes ‘orographic lift. As air rises and cools, it can’t hold moisture, so water vapour then condensed into rain clouds – and lots of them!

Many areas of southern England instead have ‘showers’ which usually fall from individual clouds, with dry sunny intervals in between. In Sussex say, you could have a downpour and the pavement will be dry within an hour.

But in Cumbria, that doesn’t happen. The ground stays wet for ages, which is why farmers have a constant battle using sprays to prevent foot rot on sheep, as the grass never dries out in winter.

The Met Office will always describe this kind of heavy rain in forecasts as ‘prolonged’ or ‘persistent’ rain.

The 16 Lakes of the Lake District

The Lake District actually only contains one ‘proper lake’ (the rest are tarns or other bodies of water). There are around 16 lakes in England’s largest National Park. Here’s a quick guide, so you know when you visit (or can win at your local pub’s general knowledge quiz!

Bassenthwaite Lake is the only real ‘lake’ in the northern Lake District, overlooked by Skiddaw mountain, with wide open views and a surprising sense of calm, considering it’s near a main road. There are footpaths and cycling routes on the western shore, where ospreys like to nest, when visiting from Africa.

Buttermere is framed by dramatic fells that rise from its shores. The easy path around the lake offers a quiet charm.

Coniston Water is set below the Old Man of Coniston (mountain), a beautiful village with a shore walk, although in summer it gets busy with paddle steamers and tourists. This is a charming place with a zero waste shop, little veggie cafes and a tiny museum.

The body of speed racer Donald Campbell (who died here in the 60s) was only recovered 20 years ago.

Crummock Water is quite remote, just 3 miles long. And popular with wild swimmers.

Derwent Water is on on the edge of the mountain town of Keswick, surrounded by wooded hills and gentle slopes. There are many islands scattered across this lake, plus a shore with easy walking paths, and views to Catbells mountain and Friar’s Crag.

Elter water is a little lake with views of Great Langdale Valley and the four peaks: Pavey Ark, Loft Crag, Pike of Stickle and Harrison Stickle. Nearby Stickle Tarn has views over Great Langdale, with rock pools cut into the mountain, and dramatic waterfalls.

Ennerdale Water is a little lake of wild beauty, with few crows. The rugged paths along the shore are popular with walkers. The area remains almost untouched, and the birds like it that way!

Esthwaite Water is a tiny lake that’s home to visiting ospreys, within walking distance of the chocolate-box village of Hawkshead, and hamlet of Near Sawrey (which was home to writer Beatrix Potter).

The surrounding area has gentle walks, to catch glimpses of herons or ducks along the shore. If you like peace and quiet, this is the ‘hermit’s lake! to discover, before anyone else does!

Grasmere is next to the village of the same name (the home and burial place of poet William Wordsworth. You can walk the lakeside to Ambleside, known for its pretty bridges and waterfalls.

Haweswater is a wild lake, which sadly was home to England’s last golden eagle.

Loweswater is another hidden lake, not a touristy place. graze and herons fish close to the shore, while buzzards fly overhead.

Rydal Water is tucked away between Rydal village and Ambleside, surrounded by woodland, trails and small beaches for ‘dipping your toes’. Walkers love the quiet paths and narrow lakeside trails, shaded by trees.

Thirlmere is on the border of the south/north Lake District, surrounded by forests. It’s near to Helvellyn mountain, one of England’s highest climbs. It’s more enclosed than other lakes, passing through pine woods and open moor.

Ullwater is a large lake (7.5 miles) that is set below the wild peaks of Helvellyn and Place Fell, and home to Aira Force Waterfall.

Wastwater is England’s deepest lake, surrounded by Scafell Pike – England’s highest mountain that is only for experienced climbers). The setting has earned this lake the title of ‘Britain’s Favourite View’.

Lake Windermere is England’s largest body of water, a narrow stretch of water over 11 miles, which sits on Bowness-on-Windermere and Ambleside. It’s currently the focus of a campaign for better sewage treatment.

The town of Windermere is not actually on the lake, it’s a few miles away. Poet Wordsworth campaigned against the building of a railway station there, saying it would ruin the quiet village. He was right. Today the station is much smaller, a good portion of it has now been turned into a Booth’s supermarket.

England’s Highest Mountains (all in the Lake District)

The Lake District is home to all of England’s tallest mountains, drawing local walkers and tourist hikers, year-round. These peaks are known for their rugged beauty and sense of wildness.

All should be approached with care, due to changeable weather (rain, wind, fog and slippery areas). Only climb mountains if you’re fit, and carrying proper gear. Don’t take dogs near high peaks or cliffs.

The Mountains of England and Wales is a guide to 254 summits in a series of 60 walks.

Standing at 978 metres, Scafell Pike is England’s tallest mountain. It dominates the western part of the Lake District and offers panoramic views that stretch far beyond the region on clear days. The summit is rocky and exposed, rewarding climbers with a true sense of achievement. Not for beginners!

At 931 metres, Skiddaw towers over the northern Lake District near the town of Keswick. Unlike Scafell Pike’s rugged peak, Skiddaw has a broad, grassy ridge and softer slopes. Its rounded profile offers a different kind of beauty.

Hikers often enjoy its straightforward climbs and the chance to experience expansive views over Derwentwater and beyond. Skiddaw feels a little quieter, making it perfect for those seeking space and peace.

Helvellyn reaches 950 metres and sits near the eastern edge of the central fells. It is famous for its narrow ridges and dramatic edges like Striding Edge, a sharp arête that tests walkers’ sure-footedness and nerve.

This mountain is a favourite for advanced hikers wanting a memorable climb with steep drops and stunning views of Ullswater and the surrounding valleys.

The Old Man of Coniston stands about 803 metres tall, making it one of the taller peaks in the southern part of the Lake District. This mountain has a rich mining heritage. Copper mines here were active for centuries, and you can still spot old mining remains along some paths.

The path starts from a car park, or from the village by foot (but this is steeper). The views at the top reward your efforts with sweeping scenes across Coniston Water and towards the central fells. This peak appeals to those who enjoy both mountain scenery and a touch of industrial history beneath their feet.

Haystacks may not be the tallest at just over 597 metres, but it holds a legendary place among Lake District walkers. It was a favourite of Alfred Wainwright, the famous fell walker and guidebook author. He found something special in its rugged charm, quiet atmosphere.

The landscape around Haystacks includes rough rock, heather moorland, and characterised ridges that make it stand out from other hills of similar height. It often forms part of longer walks in the area, linking with nearby fells like Buttermere.

Catbells is well known as a gentle introduction to the Lake District fells and a favourite for families and walkers new to the hills. Standing at just 451 metres, it offers a manageable climb with plenty of rewards.

Its paths are clear and pleasant, although there are gaps between pillars at times, so always take care.

Nearby, the Langdale Pikes form a sharp and striking group of peaks. They rise somewhat higher but remain accessible for those with moderate walking experience. These pikes, including peaks like Harrison Stickle and Pike of Stickle, have exciting ridges and dramatic shapes that are hard to miss.

William Wordsworth’s Connection to the Lake District

The pretty town of Grasmere houses the former home and burial place of William Wordsworth, one of England’s most celebrated poets. It is a bit over-commercialised now (you can imagine – like Stratford-upon-Avon with Shakespeare, everything is ‘linked’ to Wordsworth for tourism income).

If you have flower-eating dogs, know that daffodils (like all bulbs) are unsafe near animal friends. Read more on pet-friendly gardens.

But William (and his sister Dorothy) did not just confine themselves to Grasmere. Interestingly, William campaigned a few hundreds years ago against the building of Windermere railway station, believing that the influx of tourists would ruin his beloved Lakes. He was right.

His sister was also very vocal, her and a fellow writer protesting against the the found house built on the Lake District’s largest island of Belle Isle, calling it a beautiful spot that now ‘deformed by man’, and resembling a tea canister.

Wordsworth’s final home of Rydal Mount is just a short hop away from Ambleside, one of the Lake District’s prettier towns, although again a bit overrun with tourists in summer. This town apparently has the country’s busiest mountain rescue team, due to inexperienced climbers frequently getting lost of stranded.

It does remain one of the few towns, where you can literally walk from the town centre, to discover a tumbling waterfall, right on your doorstep!

All Before Me is a very interesting and unique account, of how the Lake District helped to heal one woman from a serious mental breakdown.

While teaching in her early 20s in Japan, she suffered an acute breakdown, and was even section in a Japanese psychiatric institution, until she could be flown home under escort.

Back in England, Esther (though originally from Suffolk) was offered the chance to live and work at Dove Cottage in the lake District, the home of William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy.

It was here that she began to heal. In the lives and writings of these literary siblings, she found an approach to living a life of peace and meaning, and also made lifelong bonds of friendship – and eventually love.

This book is a moving and absorbing account of the struggle to know oneself, and is intertwined with stories of the Wordsworth home and history.

Esther Rutter is a writer from Suffolk, who now lives in Scotland. She has previously worked at the Wordsworth Trust and Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. She also works as a scriptwriter and appears on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour.

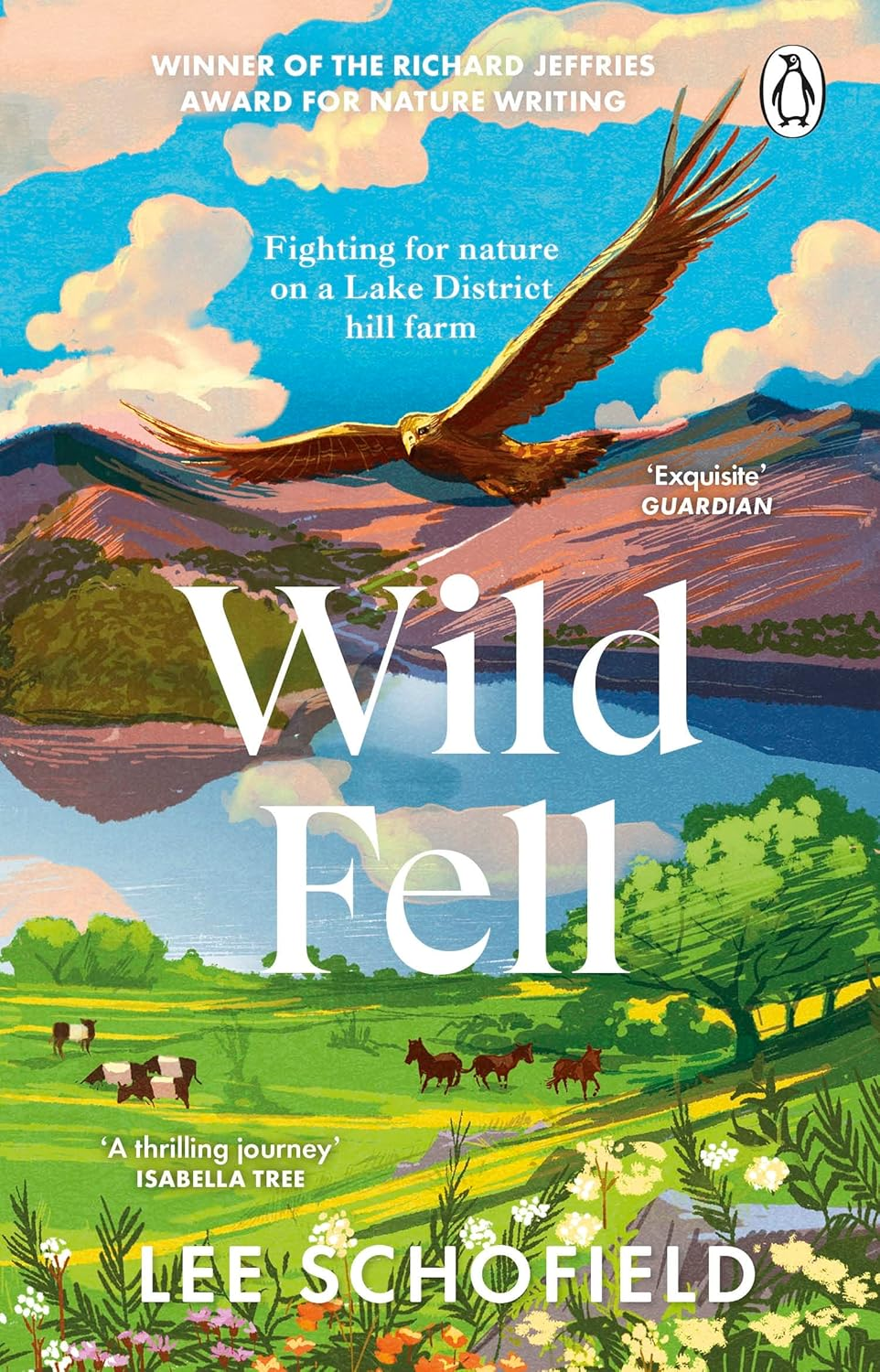

Wild Fell (restoring nature in the Lake District)

Wild Fell tells the story of how a group of people worked with farmers to rewild the remote eastern fells of the Lake District. After England’s last golden eagle died in an unmarked spot in England’s largest National Park.

The author is leading efforts to breathe life back into two hill farms, and 30 square kilometres of sprawling upland habitat. These farms sit at the edge of the region’s largest reservoir, beneath which lies the remains of a submerged village.

Lee and his team are now repairing damaged wetlands, meadows and woods, to create a landscape that is rich and wild, to support England’s rarest mountain flower and native species.

This is not just a story of nature in recovery, but how a careful balance is struck, in an area where change is not always welcomed, in areas with cherished farming traditions. But ultimately one of success.

An inspiring journey into the restoration of our uplands. I found myself turning the pages with an inward leap of joy. Reasons, intelligent, compassionate, well-informed, this is a story of hope and renewal, for both nature and farming. Isabella Tree

In a country defined as the seventh most nature-depleted on earth (in a region plagued by flooding and climate-chaos), this is a brilliant book of positive action and hope for the future. Mark Cocker

Saving nature is a tough job. In this book we get to understand why people do it: real soul-deep passion. Simon Barnes

Author Lee Schofield is site manager at RSPB Haweswater in the Land District, a landscape scale nature reserve that incorporates working farms.

Byline Times reports that Reform UK policy is to ban rewilding on land that could be used for farming. The idea being to ‘help our farmers’. But the party does not know how nature works.

What is needed is to prevent monocultures that degrade land (so no good food can grow without harmful pesticides and fertilisers). And to pay farmers for natural flood management solutions, and restoring habitats for endangered species like water voles. This would help food security, farmers and native wildlife.

Lessons from Italian and Swiss Lake Districts

England is not the only country with a Lake District. Many other countries have them too (including Switzerland and Croatia). Italy has its own Lake District in the north: there are Lakes Como, Maggiore and Lugano (the most polluted of 38 international lakes).

Italy has the same issues with raw sewage pollution and litter from over-tourism. Litter clean-up volunteers on Lake Garda recently recovered 25 tons of waste in just one year including tyres, lead batteries, glass, cans, fishing waste, shopping trolleys, road signs, bar signs and even old toilets.

In England, we have sewage pollution issues on Lake Windermere. And also lots of litter and over-tourism. Showing this is a worldwide issue, not just confined to England.

What’s different is that Italian mayors are getting tough. In some areas, they are banning the sale of plastic water bottles, and even banning tourists for some months, to protect local residents and the environment.

Italy’s northern lakes sit at the foot of the Alps, and you feel it at once. Como, Garda, and Maggiore are deep and long, caught in narrow corridors that open to wide basins. The difference is that here you’ll find terraced olive groves and lemon trees in sheltered gardens.

While England and Italy both have issues with their Lake Districts, in Italy things are moving fast. Plastic bottle bans and tourist taxes, along with better litter clean-ups.

There are much better and more frequent bus services, to discourage people from causing road gridlock in summer months. And there are strict rules for sustainable sailors, to avoid polluting the waters further.

Switzerland also has its own Lake District, which is vast compared to Cumbria. Again, the Swiss authorities keep their waters pristine clean, as they do their streets (no litter!)

Switzerland has very strong waste rules (you would get arrested, within minutes of dropping a sweet wrapper). There are even pay-per-bag schemes and strict fines, which clear recycling bins and good investment in sewage treatment. Results of lake testing are shared by cantons, so residents are kept up-to-date.

Cleaner lakes mean safer swimming, stronger fish stocks, and fewer medical warnings. They also cut costs in the long run, because preventative care beats emergency clean-ups. For visitors, the difference shows in clear shallows, no sharp smell at marinas, and sandy coves free of plastic.

Unlike in England’s Lake District, paths are maintained and people are employed to look after the lakes and surroundings, on good pay and conditions. There are strict rules to avoid feeding wildfowl (as in England, but people ignore them – they would not be allowed to get away with it, in Switzerland.

Swans, geese and ducks all have plenty of natural food in the Lakes, so there is no need to feed them. In fact, without the litter and bringing them into contact with people and roads, they likely are living in their version of ‘heaven on earth’.