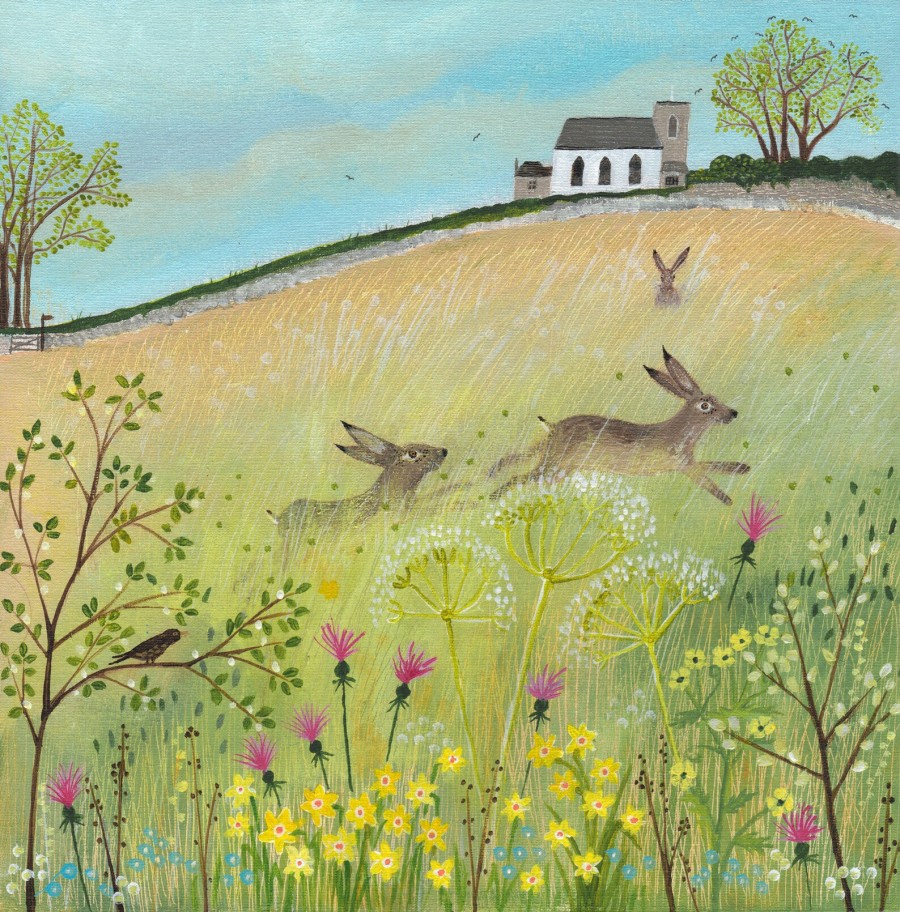

Brown hares are often seen in fields (especially if you’re on the train). Native to Asia, they have lived in England since Roman times. Larger than rabbits with bigger and longer black-tipped ears, unlike rabbits that live in brurows, hares live above ground and rest in ‘forms’ (little shallow burrows) and run in a zig-zag direction at fast speeds to escape (mostly foxes) trying to eat them.

Mostly nocturnal, hares tend to live alone, when not mating. If you see two ‘boxing hares’, this is usually a female hare fighting off a male hare that she’s not interested in! Most hares only live a few years, although a female hare may have a few litters a year (which are weaned within weeks). Due to cereals, hares are more often found in eastern England and quite rare in southwest England.

Although not endangered, hares are at risk from modern farming methods like machinery and pesticides, and are the only game species with no closed season, so are frequently hunted through the year. Mountain hares live in northern England and Scotland, with snow turning white in winter, to match their surroundings.

how to help wild hares

As with all wildlife, live a simple sustainable life. If it’s single-use plastic or made with oil, try to find something else (or don’t buy it). The more of us that try to do this, the better for all creatures and the planet.

how farmers can help hares (and other wildlife)

If you’re a farmer, visit Farm Wildlife to learn how to protect existing habitats, create field boundaries and wet features, and habitats for seeds and flowers, all of which make better habtiats for native wildlife. Leave quiet undisturbed cover for raising leverets, and some areas of grass uncut and ungrazed for hiding (and to escape from harvesting machinery). And contact wildlife-friendly farming experts.

The Hare Preservation Trust advises to break up blocks of cereal and provide more grass for grazing on arable farms and run wide strips of grass on open fields (or have pasture patches). It’s important that hares can raise leverets in quiet undisturbed areas, so leave areas uncut and ungrazed for hiding. If making silage, cut the field from centre outward so hares can escape. And leave ploughed or rough-cultivated areas left so hares can sleep. Leave 6 metre uncultivated margins around arable fields and leave cereal stubbles over winter.

please don’t hunt or harm hares

League Against Cruel Sports runs the campaign against hunting, coursing and poaching of hares. Before the hunting ban for England and Wales, one in three hunts was for hares.

what do do if you find ‘abandoned’ leverets

Most baby hares have mothers who will return to feed leverets at dusk, so leave undisturbed unless you are sure the yare in danger. If so, then contact Hare Preservation Trust or your local wildlife rescue.

a wildlife memoir of helping a leveret

Raising Hare is the touching story of a political advisor who left the city to return to the countryside of her childhood. Yet never expected to find herself raising a baby hare that she found alone and injured. She bottle-fed it and watched the hare drum on her duvet cover for attention, and even ran in from the fields when called and snoozed in her house for hours on end.

Compelled to give the little creature a chance of survival, this book chronicles their journey together, and the challenges of caring for a creature she knows she will have to return to the wild. We witness firsthand the extraordinary relationship between human and animal, and the improbable bond of trust that develops, inspiring hope when we least expect it.

I savoured every carefully chosen and perfectly polished word, and I cared so deeply about Hare that I found myself holding my breath. More than a wildlife memoir, it’s a philosophical masterpiece on our place as human beings in nature. Clare Balding

An astounding achievement. This is a great and important tale for our times. I am so pleased Chloe told us about raising Hare. I will not forget it, and nor will anyone who reads it. Michael Morpurgo

mountain hares just over the border

Read The Secret Life of the Mountain Hare. This book by Scottish writer Andy Howard looks at this captivating creature in Britain’s upland landscape. These shy charming creatures need our help, as do all wild creatures in our beautiful landscape. Iolo Williams calls Andy ‘a stunning wildlife photographer at the very peak of his profession’.

The moon climbed high above the trees beyond the far side of the field. Tawny owls stabbed at the darkness with sharp, two-syllable shrieks. Then a hare, far down the field. It ran easily out into the moonlight from the hedge on the far side, and at once it was partnered in dance by its own giant shadow. Jim Crumley