Earthworms are some of the most important creatures on the planet, that eat dead and decaying matter, to help make compost. They also form an important part of the food chain – offering food to birds, amphibians, hedgehogs, foxes and especially moles (who spend most of their days and nights doing a kind of ‘breaststroke’ with their giant claws’ to sweep through earth to find worms to feast on, and take extras back to their dens). For more info, visit Earthworm Society of Britain.

Although there are many worm species around the world, the average English garden contains around 16 types. Some live in top layers of soil, but most burrow underground. Most gardens have more worms than they know! Worms tend to come above ground after rain (or to escape from predators). You’ve likely seen seagulls doing ‘tap dances’ , tricking worms into coming above ground, to receive a tasty lunch.

Worms have no ears, eyes or teeth (like snakes, they ‘hear’ through vibrations) and can live up to a few years (they have both male and female sex organs). Alongside natural predators, their main threats are pollution (garden chemicals etc that also harm the creatures that eat the worms) and weather variations. Worms breathe through their skin so need to stay away from sunlight (or they dehydrate). But they also don’t survive long in waterlogged soil (if you see one in a puddle, gently move it to the earth, so it can burrow back underground).

It’s a myth that worms cut in two survive. Although a missing ‘tail’ may not be fatal, most organs are near the head (above the ‘saddle’). So practice no-dig gardening to protect from forks and spades. A quick ‘worm euthanasia’ with your foot may well be more humane, than letting dying worms thrash around for hours.

If planting green spaces, learn how to make gardens safe for pets (includes indoor plants to avoid). Avoid facing indoor foliage to gardens, to help stop birds flying into windows.

how do worms benefit our gardens?

Worms benefit the whole planet! Not only do they eat up dead and decaying matter, but they make ‘casts’ as they do so, cementing soil together to increase nutrients (sulphur, nitrogen) in plants which also helps retain water, for plants to grow. They also obviously provide essential food for birds and garden wildlife (including slow-worms). Although earthworms look ‘slimy’, in fact their bodies are covered with tiny hairs, which they use to burrow through and move under the soil.

Another important thing that earthworms do is preventing floods, as they help to create good soil, which is one of the main ways to help soak up rain.

Life is hard. Then you die. Then they throw dirt in your face. Then the worms eat you. Be grateful it happens in that order. David Gerrold

how we can help our garden earthworms

The best way to help earthworms is to garden organiclly. Take garden chemicals, pesticides and weedkillers to the tip (secure empty cans/aerosols and bin in normal refuse). This keeps worms, wildlife, pets and children safe. Read gardening posts for help and use safe humane methods to deter slugs and snails.

As mentioned above, gently transfer worms you find in waterlogged soil or in pavement puddles to nearby earth, so they can burrow safely back into the earth. Same with finding worms dehydrating in the sun (just gentle move to a shady spot and perhaps sprinkle some cool water from a can, to help the worm hydrate before it goes back to its underground home).

Worms like neutral soil so keep it that way by adding organic matter and leaf litter, avoiding low-calcium acidic soil and copper. Keep fresh compost away from pets and avoid use of toxic mulches like cocoa – pine mulch can cause punctures and rubber mulch can choke.

Learn about no-dig gardening (above) to avoid harming underground garden creatures. If you have to dig, then gently use hand-size garden forks to harvest or remove weeds, over heavy-handed tools (this way you can easily see creatures to avoid, before removing plants). Also avoid machinery and try not to walk on the soil (especially after heavy rain).

Don’t buy peat compost, as this is home to worms and many endangered wildlife. For homemade compost, carefully remove from bins (worms will usually be at the top munching on newly-deposited food). If you find worms in your compost, gently place them back on top of the compost heap or place somewhere safe (away from where you will turn newly-added compost). Keep hay or other ‘browns’ on top of the compost heap to cool things down as ‘hot compost’ will dehydrate worms. That’s why ‘food-digester bins are not good for wildlife, as they can ‘cook’ garden friends by getting too hot inside.

If you have a lawn, try to leave the grass a little longer. Leave clippings on the lawn, as worms will return them to the soil for you. If you find worms on grass, pop them in soil beds, to avoid them dehydrating and dying.

Keep an eye out for pets not to eat earthworms. If ingested,puppies in particular are at risk from getting roundworms (parasite eggs). Symptoms are producing spaghetti-like worms in stools. Call your vet immediately.

Many worms die with worm composters, because they require expert knowledge, to avoid ‘red wrigglers’ not dying when transferred to soil. They can also die if sent through the post (hot weather, postal strikes etc). Just garden organically and earthworms will naturally find you!

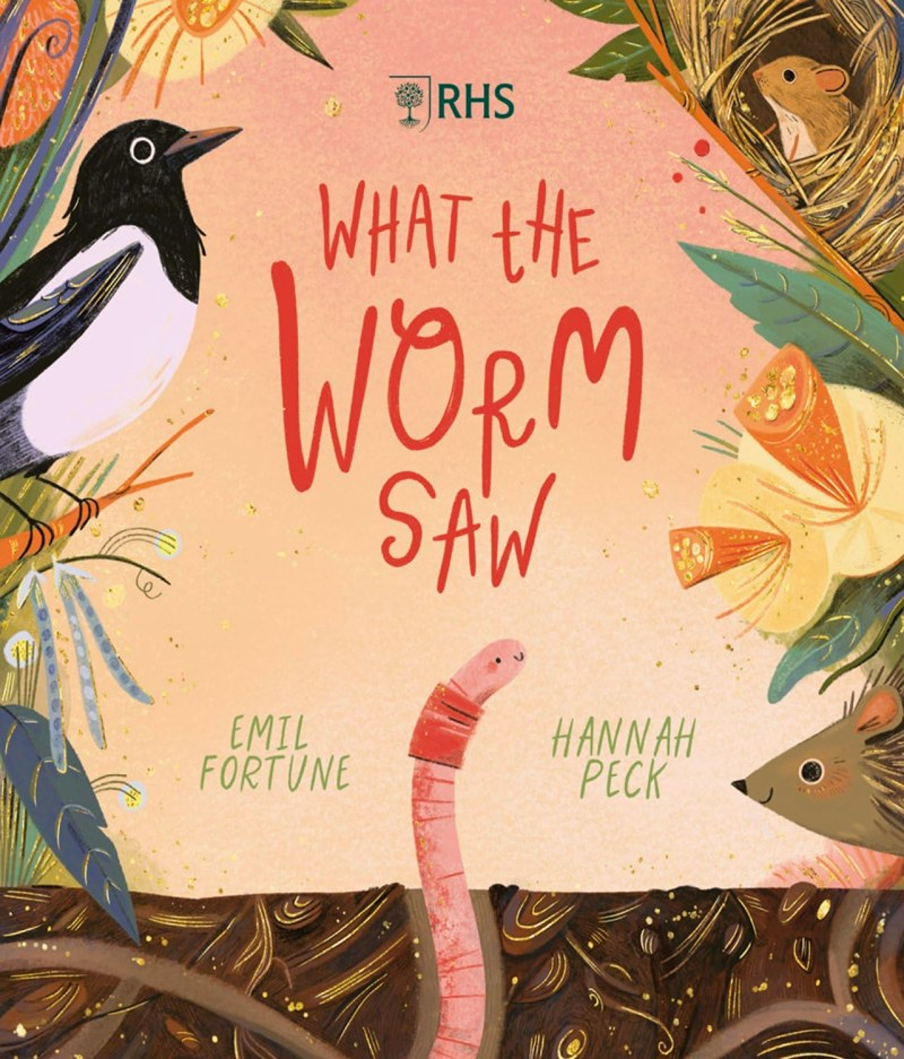

books to learn more about earthworms

The Book of the Earthworm is by Yorkshire writer Sally Coulthard. The guide to meeting ‘little engineers of the earth’, without them soils would be barren and our gardens and fields would grow no food. Worms recycle decaying plants and put nutrients back into the soil, and also provide food for wildlife. Their burrowing also helps to soak away heavy rain, preventing floods. Learn more about the world’s most industrious but little understood creatur

The Earth Moved is a wonderful book about the remarkable achievements of earthworms by an esteemed scientist who takes us underground to meet these amazing creatures who plough the soil, fight plant disease, clean up pollution and turn ordinary dirt into fertile land. This witty offbeat book talks to those who have devoted their lives to unearthing the complex life beneath our feet.

They are near the bottom of the food chain (a meal for fish and birds) while humans consume an astonishing array of what lies on the planet. But eventually, even we become food for the worms. I am left with the troubling conclusion that the worm’s survival may (in the grand scheme of things) be more important than my own. Amy Stewart