Less road traffic means safer communities for people, pets and wildlife. It’s all interlinked. If we we want an animal-friendly world, it helps to focus on creating local walkable communities with good public transit, over roads gridlocked with traffic, from lorries thundering factory-farmed foods from central distribution houses to major supermarkets. And fosters locally owned co-operative farm shops and groceries, where we have a real community spirit. Read of a free bus transport idea from Miami.

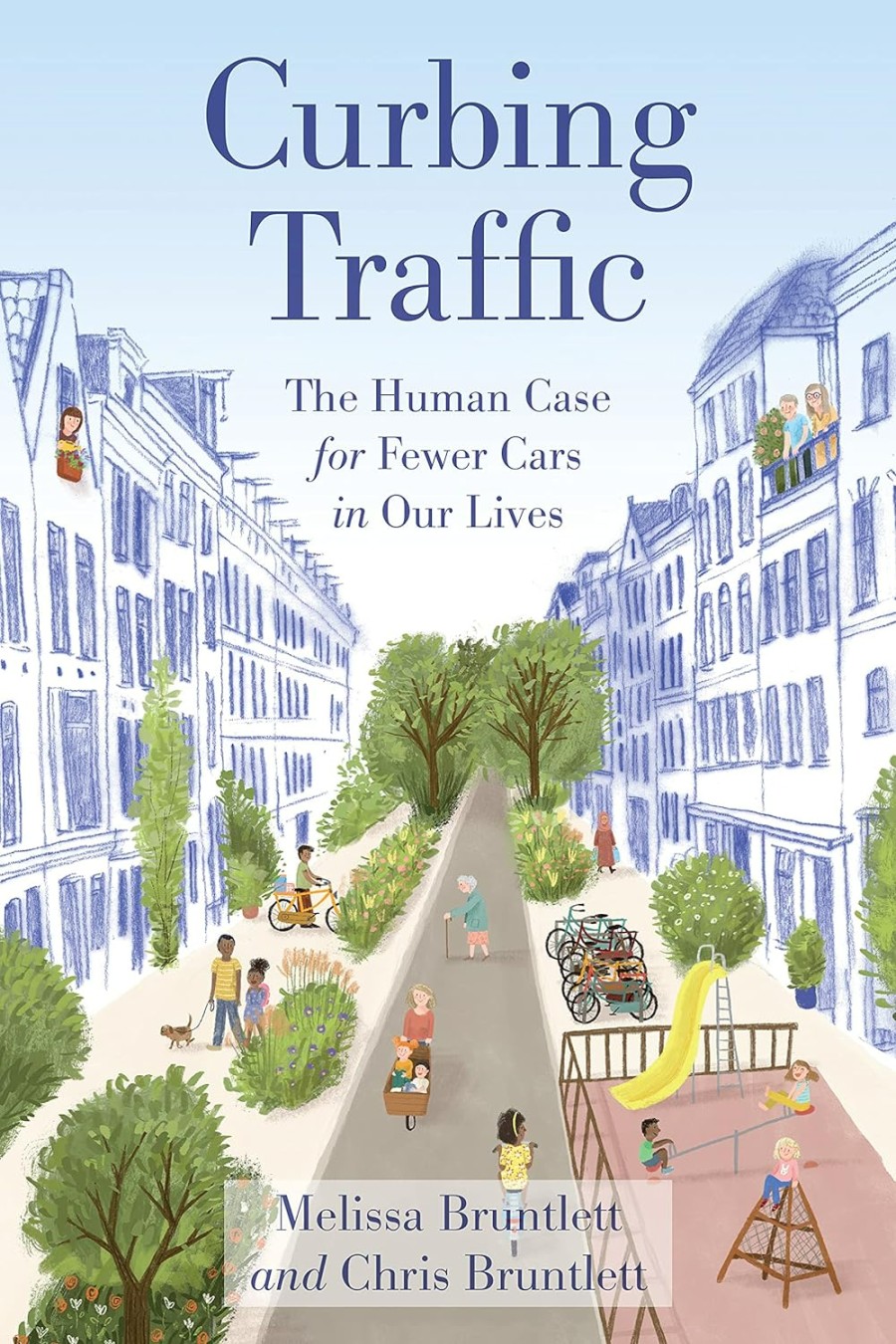

The Dutch have the right idea, with thousands of bike highways, but what happens to people who want to cycle at a more leisurely place? And what about children playing outside their homes? Or wildlife which live in local areas? Why do we make traffic (‘getting there’) of importance above all else?

Curbing Traffic is a book by a couple who moved from Canada to Delft (The Netherlands) to experience the cycling city as residents. They weave their personal story with research and interviews with experts and locals, to help readers share the experience of living in a city designed for people. The book also looks at constant focus on the car has led to people without cars (especially the elderly) to feel isolated and become dependent on others for food or company or exercise.

For green spaces, avoid toxic plants near pets (also don’t plant in railings, where nocturnal wildlife could get trapped). Avoid facing indoor foliage to gardens, to help stop birds flying into windows.

Movement is a book concerned with how we get from A to B. And what happens if we radically rethink how we use our public spaces? Could our lives change for the better? Our dependence on cars at present is damaging both the health of the planet and of ourselves. Who do our streets belong to, what do we use them for, and who gets to decide? By the end of this book, you’ll never look at the street outside your front door, in the same way again.

An entertaining overview of how the Netherlands became a mecca for cycling. The authors make a strong case for putting cycling at the heart of our transport systems, but aren’t shy about identifying flaws in the Dutch approach. Ben Coates

This book will make you think in new ways. Why have we surrendered our cities to cars? What might it be like to inhabita a space designed for people instead? It’s exciting and hopeful – this can we do! Bill McKibben

Thaila Verkade lives in Rotterdam and writes about language, transport and democracy. Marco te Brömmelstroet is chair of Urban Mobility Futures at the University of Amsterdam.

When Driving Is Not An Option looks at why town planners are always designing for cars, when around a third of people in western countries don’t even have a driving license. Most involuntary drivers are on low incomes, homeless, disabled, children, too old to drive, formerly in prison or undocumented immigrants. So we end up with towns exclusively for everyone else, which has health, environmental and quality-of-life costs for everyone (not just those excluded from planning ideas). In this book, the author (a disability advocate) shines a line on people who cannot drive, and how creating inclusive transport systems can help everyone to get around safely. Her ideas include improving pavements, offering more affordable accessible housing and creating free & discounted public transport. The book ends with a checklist of actions you can take, if you’re a walker living in a car-dependent society.

Lisbon, Simply Katy Prints

Trams are one of the best ways to get around without cars, yet England only has a few tram stations nationwide. Unlike other areas like Lisbon (where nearly everyone travels by tram). With lots of hills, the US city of San Francisco also is known for its trolley cards, pulled by cables embedded in streets. These were invented by an English mining engineer who lived in the US in the late 1800s, born out of tragedy when he witnessed five horses dragged to their deaths when they slipped on wet cobblestones and slid backwards under their heavy load.

Made of six lines, Lisbon’s tram route is comprised of bright yellow street cars, which weave through the city faster than buses, and take more people too. Unlike buses, trams can often ‘bend’ around corners and today over 60 trams criss-cross the city, ferrying both residents and tourists to where they want to go. Lisbon’s streets are naturally curvy, so this is an ideal mode of transport.

Paradoxically, England (which also has many curved streets) has very few tram systems in its cities. London has a tram system to go along with its other modes of public transport. Like trains, you need to stop before crossing tramlines as the vehicles often require a longer stopping distance than buses (as they go faster) and they are also quieter than cars, so don’t wear headphones nearby.

Nottingham has a 20-mile tram system through the city, as does Sheffield which operates 4 routes throughout the week across South Yorkshire. But the most famed tram route is undoubtedly in Blackpool, where is one of the oldest in the world, dating back to 1885 .Running for 11 miles, it carries millions of residents and holidaymakers each year, and is one of only a few that runs double-decker trams (the other main two being in Hong Kong and Egypt). Manchester also has a thriving tram system. There have been quite a few accidents on Blackpool trams, though likely more with cars.

What critics can’t understand is why our cities have so few tram systems (around 9, whilst with similar populations, France has 26 and Germany has a whopping 57 (most are in the former East Germany and have stops next to bus stops). However a new tram system to connect Leeds and Bradford is in the works, and this is due to begin in 2028. And Blackpool tram has just launched a major extension, showing the other city planners how good public transport is done.

What is mystifying is why it costs far more to build trams in England, than elsewhere. The tram extension in Manchester cost £203 million for just under 1 mile of track. Yet in France, transport planners built a 9-mile tram network for £260 million (almost a tenth of the cost). Why?