Live in the Moment: Slow Down, Enjoy Life

Living in the moment is much easier said than done. But at least if you make an effort, you are sure to feel better within a few weeks. It’s about finding comfort with who you are, what you have, and where you are right now. Without having to chase endless goals, in order to feel happy or at peace.

For years, the idea of a quiet Sunday has stood out in England. Many saw it as a time to rest, spend time with family, or simply pause from a busy week. The campaign to Keep Sundays Special grew out of this feeling that Sundays shouldn’t become just another workday.

Shops often stayed shut or opened for fewer hours, and the streets felt calmer. People valued having a day to recharge or share a meal together. In this post, you’ll get a look at the story behind the campaign, what Sundays used to mean up and down the country, and why many believe it’s worth keeping that slower pace, even now.

Not many realise that you do have certain legal rights, if you don’t want to work Sundays. Citizens Advice has good info. But if you refuse – they may find some other way to fire you?

Stores over 280 square metres are now allowed to open for 6 continuous hours on Sundays, but not allowed to open on Easter Sunday or Christmas Day.

Long Living People Don’t Work Sundays

You may have heard of Dr Ellsworth Wareham, the vegan cardiologist who continued his practice well into his 90s (he said the only problem was when the patients saw how old he was, just before they went under the knife!)

Although his diet and lifestyle played a key part, it’s interesting that he was from the Californian town of Loma Linda.

This town is religious (Seventh Day Adventist). So apart from emergency services, everything shuts down on Sundays, and people do nothing. And the town has the highest longevity of any town in the USA.

Do not let Sunday be taken from you. If your soul has no Sunday, it becomes an orphan. Albert Schweitzer

The Igbo (who live mostly in Nigeria) have a four-day week (the second day Orie is a holy day of obligation when farmers rest).

On Ghana’s coastline, no fishing is allowed on Tuesday, to give the sea time to replenish. Mohandas Gandhi took each Monday as a day of total silence. Try it. One day a week. It could be merely a question of doing nothing. Jonathan Schorsch

The Influence of Faith

Faith, especially Christian faith, gave Sunday its special role in England. For centuries, church bells marked the start of a slower day. Families would dress up and walk to church together, setting aside work and chores. It wasn’t just about the service. The day carried a simple message: take time to rest and reconnect.

In Christian practice, Sunday is special because it marks the resurrection of Jesus. Early Christians chose this day for worship to set themselves apart from Jewish Sabbath traditions (which fall on Saturday). For many, that Sunday rhythm became woven into daily life. Long before shops or football matches, the quiet of Sunday held a different weight thanks to church traditions and rest.

Tradition and Community

Tradition kept Sunday different even beyond faith. Villages and towns would plan around it. Walks and family visits were the norm. In some places, you could almost hear the quiet—little traffic, closed shops, a distant sound of church choirs.

The slower pace let people recharge and spend time together in ways that can be hard to find in a busy week.

Some of these traditions still linger. Afternoon teas and family dinners often happen on Sundays. Many older people remember when even chores took a back seat. You might spot friends at the park or families strolling after lunch. These customs became part of the weekly rhythm that people looked forward to.

Protecting Worker Rights

No one wants to feel like they’re always on call. In England and across much of Europe, the right to rest is often seen as basic as fair pay. Allowing workers Sunday as a day off helps draw a line between work life and home life.

- Right to Refuse: Laws in some countries mean staff can say no to Sunday shifts without losing their jobs. Germany’s “blue laws” keep most big shops closed on Sundays. Workers in Austria and Poland also get this guaranteed pause, making it clear that time off matters as much as time at work.

- Balancing Act: Not everyone has control over their schedule. With more places open every day, staff, especially in shops, often feel pressured to work weekends. When Sunday stays special, it stops bosses expecting round-the-clock cover.

- Fairness Across Sectors: Those in care or emergency jobs may still need to work, but keeping other industries closed helps cut the pressure and shows respect for everyone’s time.

Supporting Mental Wellbeing

A pause in the weekly rush can work wonders for your headspace. Mental health experts talk all the time about the need for downtime. Sundays give people a built-in reason to switch off.

Benefits include:

- Lower Stress: Without the hum of everyday business, people can breathe easier. No last-minute work emails or calls pulling you away from home.

- Stronger Bonds: Time off together brings families closer. Parents get the chance to play with their children, have lunch with relatives, or go for a walk in the park.

- Time to Reset: Quiet Sundays let people follow interests, reflect, or just nap. Over time, this break can cut down on burnout and make Monday feel less like a mountain to climb.

Examples Across Europe:

- In Greece, Sunday shop closures still hold in most places. Families often spend the afternoon outside or at local cafés.

- In Poland, schools and businesses slow down, giving entire towns a breather every week.

Local Shops and Less Consumer Pressure

Protecting Sundays does more than help workers and families. It can also give life back to the high street.

When supermarkets and chains stay open all week, small local shops struggle to keep up. Limiting trade on Sundays helps even the playing field. Owners get a break with their families, and staff don’t have to sacrifice their weekends just to stay afloat.

Key outcomes:

- Community First: Local shops can survive when they aren’t forced to compete nonstop. That means more unique stores, friendlier faces, and money staying in the neighbourhood.

- Reduced Consumerism: A quieter Sunday puts less pressure on everyone to shop for the sake of it. Instead, people use these hours for hobbies, home-cooked meals, or chatting with neighbours.

- Warmer Feel: Anyone who’s walked down a high street in Austria or Germany on a Sunday knows the calm. Coffee shops are full, but shops are shuttered. Friends gather without the urge to rush to the next sale.

What Makes a Restful Sunday?

Time Spent Outdoors

Stepping outside on a Sunday morning can feel like hitting a reset button. Parks fill up with families, friends meet for walks, and the simple act of breathing fresh air is enough to make anyone feel lighter. Nature works its quiet magic best when you let yourself slow down.

People find calm in many ways:

- A walk in the local park or woods: Even half an hour outside can make you feel brighter. You might spot neighbours out for a stroll or meet someone walking their dog.

- Bike rides: A gentle cycle through the countryside or along quiet streets feels different when you’re not racing the clock.

- Gardening: Potting up some seeds or tidying the garden gives a sense of purpose, but still lets you take it easy.

If planting green spaces, read up on pet-friendly gardens and wildlife-friendly gardens. If planting trees, know of trees to avoid near horses (including yew, oak and sycamore).

Cooking and Sharing Food

Food brings people together, and Sunday offers a perfect reason to gather round the table. The smells tumbling out of kitchens speak of comfort and tradition without much fuss. When meals are shared, they linger longer and feel more special.

- Families pull together for a Sunday veggie roast or a slow breakfast.

- Baking bread or cakes becomes a group effort, not just a chore.

- Lunch spills into the afternoon, with stories, laughter, and sometimes a dozy nap.

Small Pleasures and Simple Routines

Slower Sundays shine when you let yourself enjoy life’s small comforts. It might mean reading a book in the sun, listening to music, or just enjoying a quiet cup of tea. Setting aside time for these simple habits can make a big difference.

Here are some ideas that work for many people:

- Write a letter or postcard to a friend instead of firing off a quick text.

- Tidy a small space at home while listening to your favourite album.

- Do a puzzle, draw, or knit for a bit of quiet focus.

- Switch off your phone for a couple of hours and notice the difference.

Community Events and Local Gatherings

A restful Sunday doesn’t have to be spent alone. Plenty of people find joy in joining community events. Local fairs, Sunday football matches, open gardens, and car-boot sales all offer low-key ways to spend time together.

Local noticeboards or online groups often list what’s on. Attending even one event here or there helps build ties and makes the day feel brighter. Simple pleasures like a stroll to a farmers’ market or a chat with someone at a car boot sale are ways to feel part of something bigger, without having to do much.

Doing Less to Enjoy More

Restful Sundays work best when you let yourself press pause. This can look different for everyone, but the idea is to do a little less so you can enjoy a little more.

Some practical ways include:

- Skipping the big shop and using what’s in the fridge or cupboard.

- Leaving chores for another day if they aren’t urgent.

- Saying ‘no’ to anything that feels like another job, unless it brings peace or joy.

Giving yourself permission to step back means you’re more likely to enjoy what you do choose. A restful Sunday doesn’t need to be perfect. It just needs to be yours, done your way.

Whatever you choose, a truly restful Sunday is about turning down the noise, even just a little. By doing so, you can keep the spirit of Sundays alive in a way that fits your life today.

Preparing Your Heart for Weekly Mass

Bath Abbey is a unique building with grand stained-glass windows, honey-gold stone and beautiful fan vaulting, creating magnificent light. A place of worship for over 1200 years, it still holds regular services throughout the week.

This historic holy place also features unique ‘ladders of Angels, created after the Bishop of Bath had dreams of Angels descending and ascending from Heaven.

One Sunday at a Time is a beautiful colour book to help you prepare for 10 minutes each week, to help experience the Sunday Mass more fully, and deepen your love for the Word of God.

An ideal resource for Catholics who wish to get more out of Mass, learn to understand the Bible better, receive God’s grace and learn how to make the liturgy come to life in a whole new way.

In this book you’ll find brief summaries of Mass readings for Sundays and engaging reflections to draw your attention to primary themes and common threads each week. Also find explanations of key Greek and Hebrew words in Biblical texts.

The book also includes prayer and a weekly challenge to help put into practice the message of each week’s readings in daily life. Author Mark Hart is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame and research fellow at the St Paul Center for Biblical Theology. He lives in Arizona, USA.).

Notice Your Surroundings

When you wake up, listen to the birds and look at the nature right outside your door. What colours and shapes can you see in the natural landscape.

Focus on One Thing at a Time

When you multitask, you split your mind and miss out on the present. Try to give your full attention to whatever you’re doing, whether you’re eating, listening to music, or going for a walk.

This helps you enjoy life as it happens, instead of speeding through it.

Slow Down Your Daily Activities

Rushing stops you from enjoying simple things. Try to walk slower, chew your food, and breathe deeply when you can. Notice how much more you take in when you give yourself the chance to go at your own pace.

Put Away the Phone

When you reach for your phone, check if you really need it or if you’re just filling a quiet moment. If you don’t need it, set it down. Give your attention to the people, sights, and sounds right in front of you.

Life isn’t happening through a screen.

Accept What You Feel

It’s tempting to push away feelings you don’t like, but ignoring them never helps. Take a moment to recognise your emotions, good or bad, without judging yourself. Every feeling is part of your experience, and accepting them can help you feel at peace.

Limit Worry and Regret

It’s easy to replay things from the past or worry about tomorrow, but these thoughts don’t change anything. When you notice your mind drifting to regrets or worries, bring your focus back to what’s happening now. Come back to the moment, as many times as you need.

Take Deep Breaths

Your breath is always with you. Slow, deep breaths can calm your mind and bring you back from distractions. Try a few deep breaths whenever your thoughts start to race or you feel tense.

Connect with People

Being present isn’t just about being alone with your thoughts. When you speak to someone, give them your full attention. Listen to what they’re saying without planning what you’ll say next. This kind of attention can make your relationships feel deeper and more rewarding.

Appreciate Simple Pleasures

A good cup of tea, a cosy seat, a sunny spot—these little moments often make up the best parts of the day. Take time to notice and enjoy them. Gratitude for small things anchors you in the now.

Let Go of Perfection

The moment you’re in doesn’t need to be perfect. Let go of chasing flawless experiences or perfect happiness. Life is full of small flaws, surprises, and changes, and that’s what gives it meaning. Accept what comes, as it comes.

Spend Time in Nature

Natural spaces slow you down. Even a walk in a small park or standing under a tree can help you reconnect with the present. Listen to the birds, watch the clouds shift, or feel the wind. Let nature show you how to pause.

The Wisdom of Teaching Children Aesop’s Fables

Aesop’s Fables are a collection of ancient stories, each with a moral tale to tell. It would be wonderful if ‘they came back into fashion’. Many of the stories features creatures from the natural world, to both educate and inspire.

Wildlife TV presenter Hamza Yassin recently said he would love it, if children were able to name five trees, rather than five Kardashians.

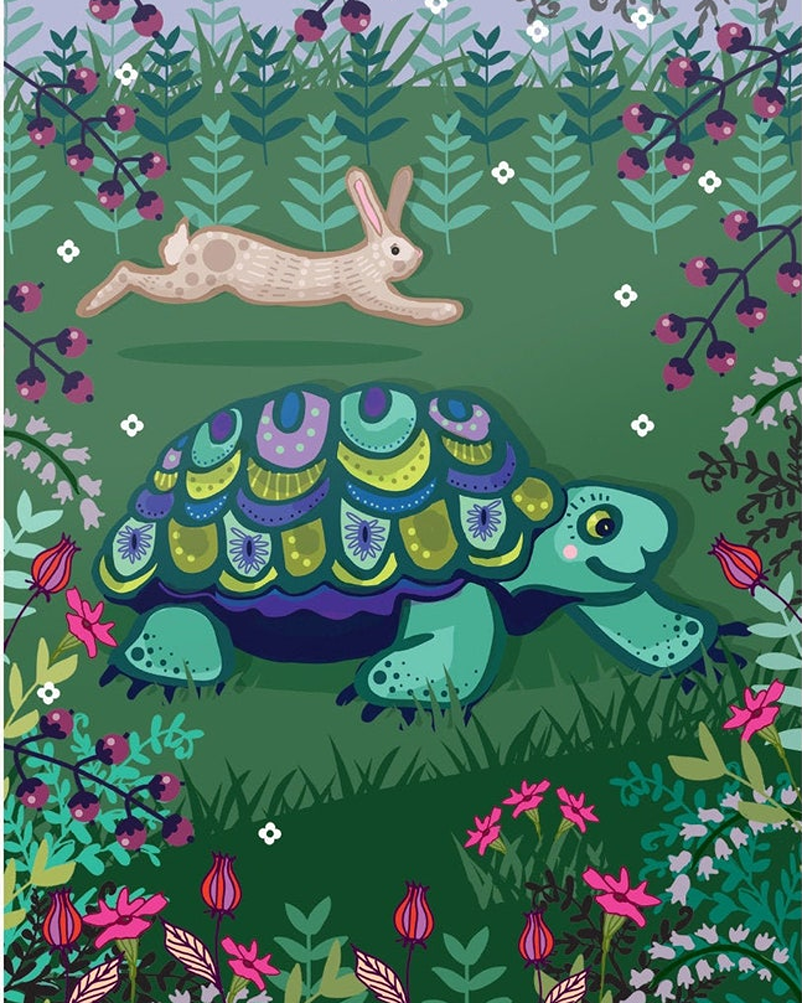

Lessons from the Tortoise and the Hare Fable

The Tortoise and the Hare was one of Aesop’s fables, a story with a moral compass. In this case, that you often get further, when you slow down. It’s a lesson that many of us could learn, in today’s fast-moving society.

A swift hare brags about his speed to other animals. But the slow tortoise challenges the hare to a race. Although the hare easily pulls ahead to victory, he decides to stop and take a nap. While the slow and steady tortoise makes it to the finish line first.

You may deride my awkward pace. But slow and steady wins the race. Tortoise

This fable is known worldwide, with different versions. In Native American culture, it’s a hummingbird and crane, that agree to race from ocean to another. Against, the tiny fast hummingbird stops at night to sleep, while the crane flies overnight and comes in first.

Other fables that you may be familiar with include:

- Mercury and the Woodman (honesty is the best policy)

- Milkmaid and her Pail (don’t count your chickens, before they are hatched)

- The Ant and the Grasshopper (be prepared for the days of necessity)

- The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing (appearances can be deceptive)

- Father and His Daughters (you can’t please everyone)

How the Slow Food Movement Began in Italy

Although sometimes it’s good to make a meal in 15 minutes, often it’s nicer to spend time savouring a slow meal. The worldwide ‘slow food movement’ was born in Rome, when local Carlo Petrini, was dismayed when a branch of McDonald’s opened up in his favourite piazza, near the Spanish Steps.

He said that the day was when ‘the umbilical cord that once connected the farmer and consumer was cut’.

In Italy, the worldwide co-operative movement (not the same as co-op supermarket!) is strong. Especially in the green city of Bologna. People open shops and restaurants early, close for several hours to have a proper lunch and nap, then open again until around 8pm. Then go home for another proper meal, conversation, a little wine perhaps, and a good night’s sleep.

That’s the opposite of England’s ‘work till you drop’ philosophy, and 9am to 5pm culture. Which makes time for a quick sandwich from Tesco Express, and perhaps a fizzy drink on the run.

As a result, Italians (and French, Greek and Spanish people) all tend to have better physical and mental health. What can we learn from these countries, in order to slow down our food and lifestyle?

Carlo Petrini and the Early Protests

Carlo (who works as a journalist and came from Bra, a small town in Piedmont that borders the Alps near France and Switzerland) wrote about food for a living. He and others began peaceful protests against the invasion of fast food (it’s interesting that in Italy, McDonald’s sell very different food – pizza slices and salads, though this is still done better by locals!)

The national and then international media got involved, asking local people why they were protesting against hamburgers. Petrini replied that this was about choice, dignity and taste. Alas, since then even Vatican City rents out a building to McDonald’s for around 30,000 Euros a month. But there are still protests there, including by some cardinals (one down from the Pope, one up from a bishop!)

The slow movement soon began practical campaigns. Cooking meals from local ingredients, and inviting people to eat them slowly, over good wine from local vineyards. Schools were inviting growers to talk to them about soil and seasons, and where their food came from. Restaurants began to add notes about producers, on their menus.

The Birth of the Slow Food Manifesto

Next (three years after the first McDonald’s landed in the Rome piazza), the Slow Food Association launched with a manifesto presented in Paris. That framed eating as a ‘respect for land and labour’. It called for the protection of biodiversity, support for sustainable farming and the right to enjoy good food.

It also spoke up for sustainable farmers and artisans, and for eaters who wanted to know where their food came from.

Soon groups were being launched worldwide, including in England. If we save heirloom beans, we keep flavours on the plate, and resilience in the field. If we pay a fair price for local food, we protect artisan foods and crafts. If we eat with attention, we connect our tables to the people who sit at them.

Core Principles of Good, Clean, and Fair Food

The movement rests on three simple words.

- Good: Food should taste good, use quality ingredients, and reflect place.

- Clean: Production should respect the environment and animal welfare.

- Fair: Prices should reward producers and be accessible for eaters.