Today England is all about ‘fast food’. Whether that’s fast food restaurants, supermarket ready-meals or ‘meals ready in 15 minutes’. But the slow food movement is growing in popularity, and it started in Italy! When local man Carlo Petrini was appalled that a branch of McDonald’s set up in his favourite piazza, near the Spanish Steps in Rome. He said that day was when ‘the umbilical cord that once connected the farmer and consumer was cut’.

The worldwide co-operative movement (not the same as co-op supermarket!) started here, where workers genuinely own the company they are employed at.

The interesting thing is that in Bologna (where the movement is strongest), people work less but are more affluent. They practice the opposite of the ‘work till you drop’ philosophy.

They open shops early, close for several hours to go have a proper lunch and nap, then open again until around 8pm. Then go home for another meal, wine, conversation and sleep.

In England, we are still opening shops at 9am and shutting them at 6pm. This leads to most people having not much of a life ‘outside work’, and grabbing a quick plastic-wrapped sandwich for lunch, instead of enjoying a proper meal.

What can we learn from Italy (and other European countries)? In how they balance life and work, shut for a few hours to eat and rest properly, and tend to be all the better for it (physical and mental health, family time and better economics). Who in England is creating laws, to suggest we continue a working lifestyle – that obviously isn’t working?

The Origins of Slow Food in Bra, Italy

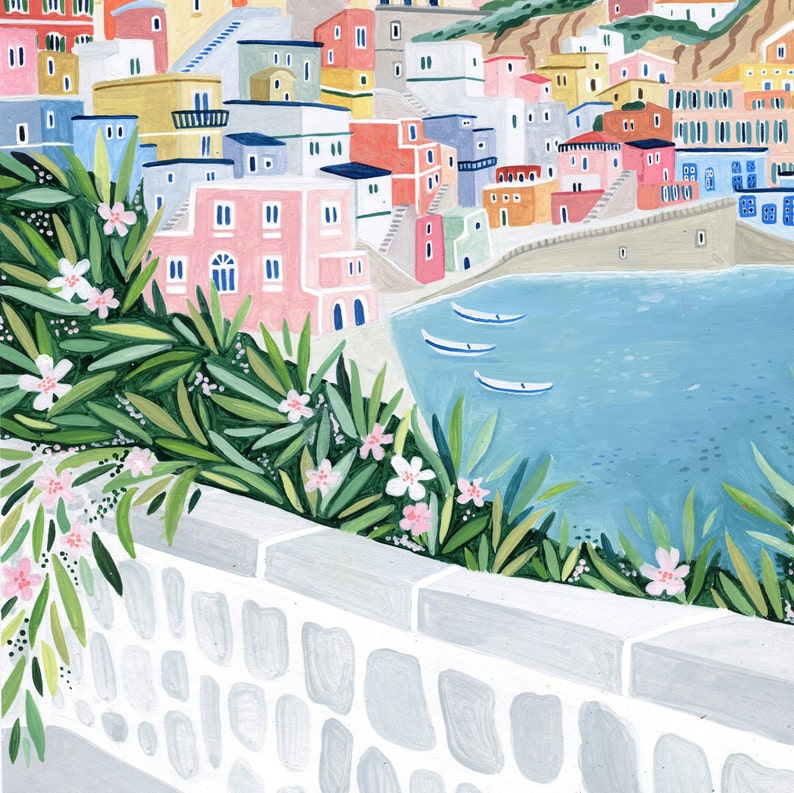

Bra, a small town in Piedmont, sits between gentle hills and rows of vines. It is a place where markets still anchor the week and where local wine, and hazelnuts have deep roots. Nearby towns guard white truffles like treasure. Names like Barolo and Barbaresco are not just labels, they are histories in a bottle. Food here carries memory.

In 1986, fast food chains moved into Italy with speed, most famously in Rome near the Spanish Steps. The sight of burgers and fries near such a symbol of beauty upset many Italians. In Piedmont, people in Bra and the surrounding Langhe felt that same jolt. Their culture was built on slow cooking, seasonal produce, and small producers.

The first public actions were not grand. They were gatherings, talks, and protests that mixed humour with sharp critique. People marched, carrying bread and wine as symbols of what they wanted to protect. They spoke about long lunches, family recipes, and the value of knowing who made your food. They asked a clear question. If Italy loses its taste, what does it gain?

Residents in Bra rallied around their traditions. They pointed to what was at stake. The Alba white truffle depends on clean woods and skilled hunters. Nebbiolo grapes do not thrive in a rush. The argument was not only about one restaurant. It was about the future of a whole way of life.

Carlo Petrini and the Early Protests

At the centre stood Carlo Petrini, a journalist from Bra with a deep love of food and a knack for organising. He wrote about gastronomy, but he also worked with cultural groups and civic clubs. He saw food as culture, not just calories. That view shaped what came next.

In 1986, protests against fast food drew wide notice. In Rome, demonstrations highlighted how foreign chains might erode local habits. In Piedmont, Petrini helped turn that spark into steady action. Marches and public meetings used playful signs that put vineyards ahead of burgers, and pasta ahead of speed.

Local producers walked beside students and chefs. The mood was lively, yet firm. Reporters came to see why a small town cared so much about lunch.

The response was quick. Newspapers ran photos of banners and baskets of bread. TV crews asked why people would protest a hamburger. The answer, said Petrini and his peers, was not about banning anything. It was about choice, dignity, and taste. That clear message drew allies from beyond Piedmont and set the stage for a movement with staying power.

Building Momentum in the Late 1980s

Protests soon shifted into planning. Community leaders, cooks, and farmers met in halls, cafés, and wineries. They mapped what needed saving, from seed varieties to cooking methods. They set up local groups to promote seasonal cooking and direct links between producers and buyers. Education became a key tool.

Early events were joyful and useful at once. Tastings paired wines with regional dishes, and talks explained why biodiversity matters to flavour. Schools invited growers to speak about soil and seasons. Restaurants added notes about producers to their menus.

These gatherings moved the cause from protest to proposal. The message changed shape. It was not only against fast food, it was for a shared food culture rooted in place. That turn from anger to action laid the groundwork for a formal identity that could travel beyond one town.

The Birth of the Slow Food Manifesto

In 1989, the Slow Food Association launched with a manifesto presented in Paris. The text set out a bold defence of taste and time. It framed eating as a pleasure tied to respect for land and labour. One line captured the spirit: “A firm defence of quiet material pleasure is the only way to oppose the universal folly of Fast Life.” Another argued for “a new culture of food” that values diversity and conviviality.

The manifesto highlighted three linked aims. It called for the protection of biodiversity, support for sustainable farming, and the right to enjoy food without guilt. It spoke for farmers who keep old seeds alive, and artisans who refuse shortcuts. It also spoke for eaters who want to know where their food comes from.

The Paris launch helped the idea spread. Groups formed across Italy, then in France, Germany, the UK, and beyond. The message resonated because it tied big issues to everyday acts. If we save heirloom beans, we keep flavours on the plate and resilience in the field. If we pay a fair price for local food, we protect a craft and a landscape. If we eat with attention, we connect our tables to the people who fill them.

Core Principles of Good, Clean, and Fair Food

The movement rests on three simple words.

- Good: Food should taste good, use quality ingredients, and reflect place. Example: protecting Barolo wine means defending careful vineyard work and long ageing, which give depth and character.

- Clean: Production should respect the environment and animal welfare.

- Fair: Prices should reward producers and be accessible for eaters. Example: direct sales at markets or community schemes can give farmers a stable income and offer buyers fresh food at honest prices.

Early Challenges and Italian Expansion

Growth was not smooth. Funding was tight, and some in big agriculture dismissed the effort as nostalgic. Others worried that talk of taste would exclude those on low incomes. The response focused on concrete projects and wider access.

One key tool was the creation of presidia, small projects to protect endangered foods, breeds, and methods. In Tuscany, teams supported old grains like Verna wheat, which thrive in poorer soils and make fragrant bread. In Emilia-Romagna, groups worked with producers of traditional balsamic vinegar, guarding long ageing in wooden barrels.

Good Food, Good Wine, Good Shoes!

Food is life in Italy. Means are an event, with fresh fruits, and a little good wine with good Italian food.

Like France, stylish Italians pay a bit more for quality skincare and clothing (you won’t find shops selling cheap clothes that fall apart and are made in the Far East).

Italy now has some of the world’s best brands of vegan shoes made with apple leather, a waste product from the apple industry in Milan (and some also make grape leather, from wine skins!)