England is home to a rich network of rivers, which all flow into one of our seas. England’s longest river is the Severn (220 miles from Wales to just outside Bristol). The Thames is often thought of as a ‘London river’ but actually begins in The Cotswolds and flows through Oxford right out to the North Sea.

Rivers don’t just provide homes for wildlife and fish, but also provide us with fresh drinking water (through natural filters of ‘chalk streams’ for people and farmers). Chalk streams are quite rare (around 200 mostly in England, and a few in France). But litter, pollution and sewage are harming rivers and wildlife that call them home (swans, otters, endangered water voles and kingfishers).

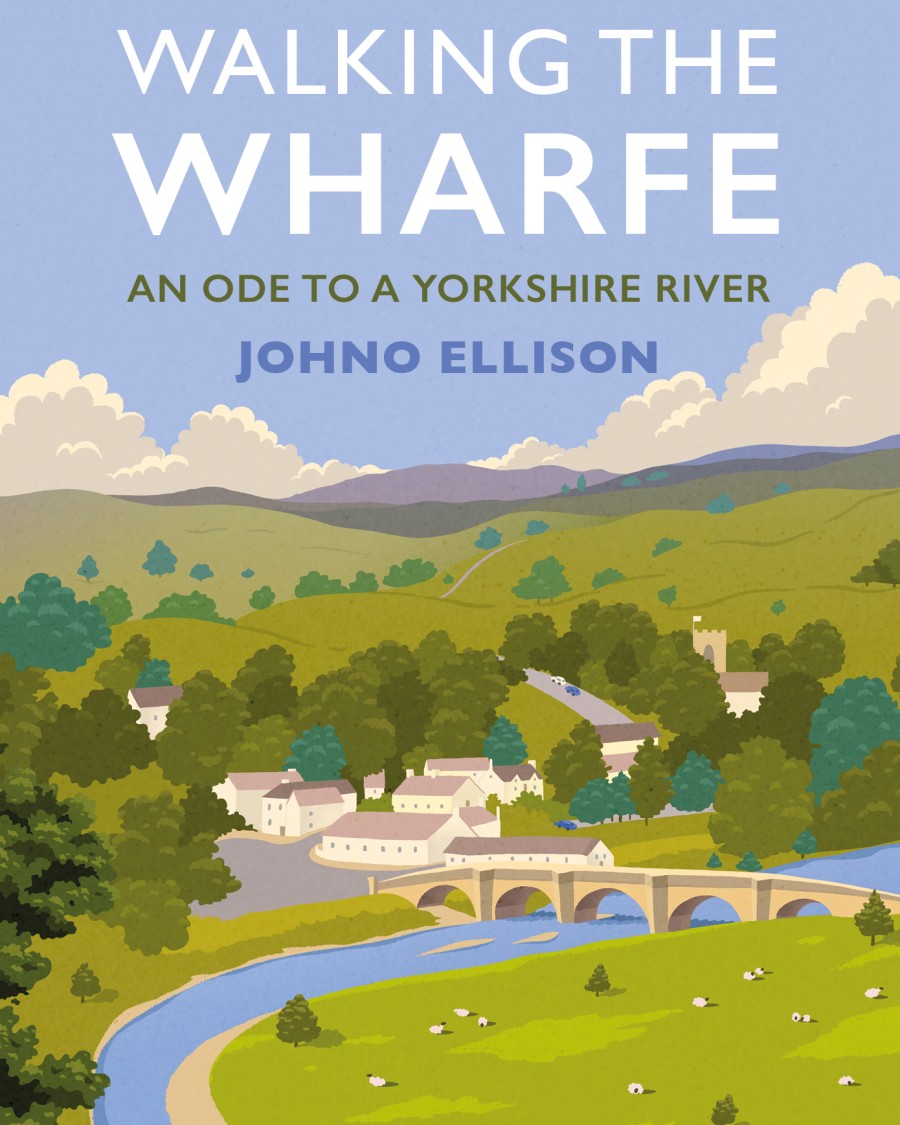

Walking the Wharfe sees writer Johno Ellison return from living abroad to walk the length of the waterway where he grew up. Retracing the steps of Victorian writer Edmund Bogg, he walks upstream from the Vale of York to find Victorian spa towns and rare red kites (and otters) who have returned, thanks to conservation initiatives. Seduced into wild swimming in a chilly river (not the section notorious for reportedly drowning everyone who has ever tumbled into it), this book confirms that lesser-known parts of our small island, can hold their own against touristy areas.

preventing raw sewage entering our rivers

England (and Wales) has around 18,000 sewer overflows which release untreated water after heavy rain. Water companies say that raw sewage entering our rivers is due to freak weather, but critics say it’s because the companies focus on shareholder profits over investment in modern sewage treatments. It’s true they ‘invest millions’. But with huge profits, they need to invest more.

In 2023, raw sewage was discharged 23,000 times near Manchester (the worst year for storm water pollution) and similar overflows happened in Preston, Blackburn and in the River Avon (the third most polluted river in England). Anglian Water recently received the largest-ever environmental fine (for allowing millions of litres of untreated water to flow into the North Sea). And in Cumbria, campaigns are afoot for better investment to stop raw sewage ending up in Lake Windermere. Some water boards are not in local hands ((Northumbrian Water is owned by a company the other side of the world).

preventing polluting agricultural run-off

The other main pollutant to our rivers is agricultural waste from the farming industry. Although phosphates for laundry detergents are banned in the UK, farmers use (almost always imported) phosphorus. This causes algae, which robs rivers (and creatures that live in them) of oxygen. As 70% of England’s land is for farming use, obviously the answer is for them to revert to organic methods of growing food. You can download free best practice sheets for farmers.

steps we can all take to help our rivers

- Don’t flush anything down the toilet apart from pee, poo and toilet paper (avoid ‘luxury brands’ that can block drains and cause floods). Never flush feminine care items (even organic), just bin them.

- Use a cooking oil recycling bin . Pouring cooking oil down sinks blocks sewers, causing emergency discharge.’Fatty McFatberg’ was filled with wet wipes, tampons and condoms, all flushed down London’s toilets.

- Whether you own a garden or a farm, securely bin chemicals/pesticides (take them to toxic waste) and grow organic food instead (shop organic too).

- If you go for riverside walks, don’t drop litter (anglers can use a monomaster to keep fishing tackle safe until they fine a recycling bin). If you sail, read tips to be a sustainable boater.

- For old homes and recent renovations, check with a qualified plumber for drains misconnections (rainwater and wastewater from sinks/toilets all go into rivers, without the latter being treated). This is easily fixed.

- Use biodegradable (ideally unscented) household cleaners (avoid essential oils for pregnancy/nursing or affected medical conditions, nor near young children and pets – never pour neat essential oils down sinks, they can harm harm aquatic life). Especially important for septic tanks (not connected to wastewater systems).

report sewage pollution immediately

Report sewage pollution (dead/gasping fish, bad smells, sewage litter (sanitary pads, wet wipes) or brown water (sewage water is grey or black – Surfers Against Sewage says if the ‘water looks like shit – it probably is’). Note the date, time and postcode, ideall with photos and videos. Sewage hotlines are open 24 hours.

choose permeable paving for town planning

Choose permeable paving (prevents pooling and flooding). Concrete and fake grass (which does not support wildlife and gets too hot for dogs in warm weather) cannot absorb rain (unlike real grass). Portland city (US) uses bioswales (plants) to absorb pollutants in rain, to prevent floods.

books to read more about England’s rivers

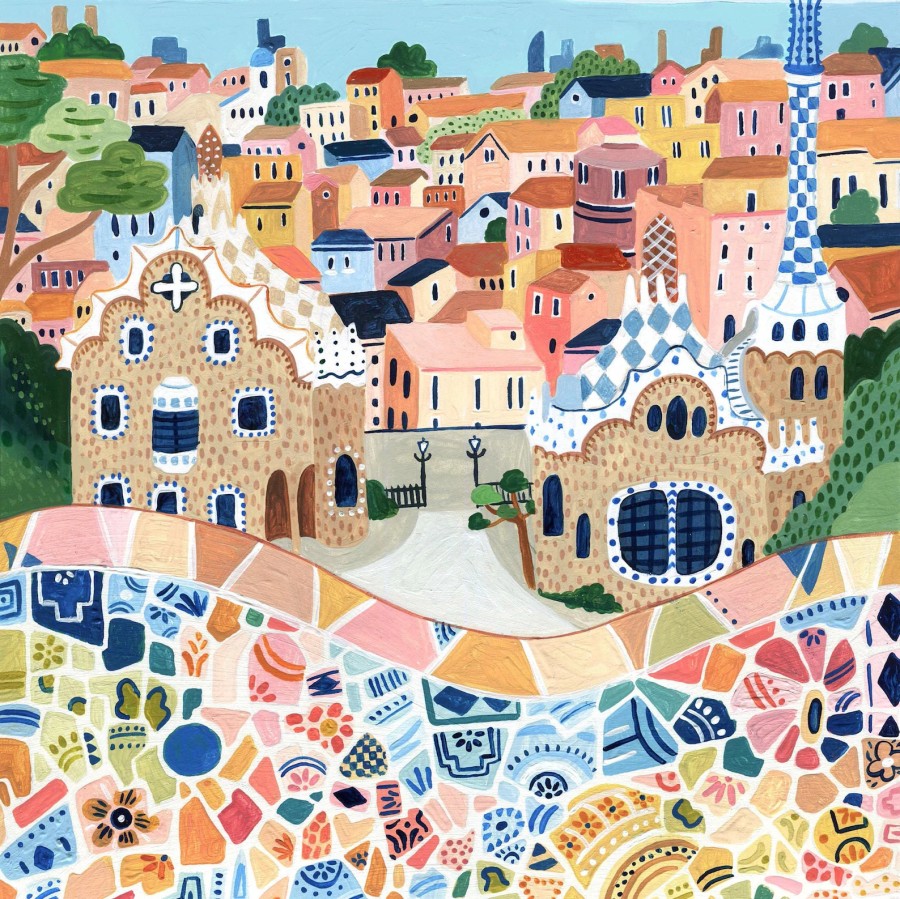

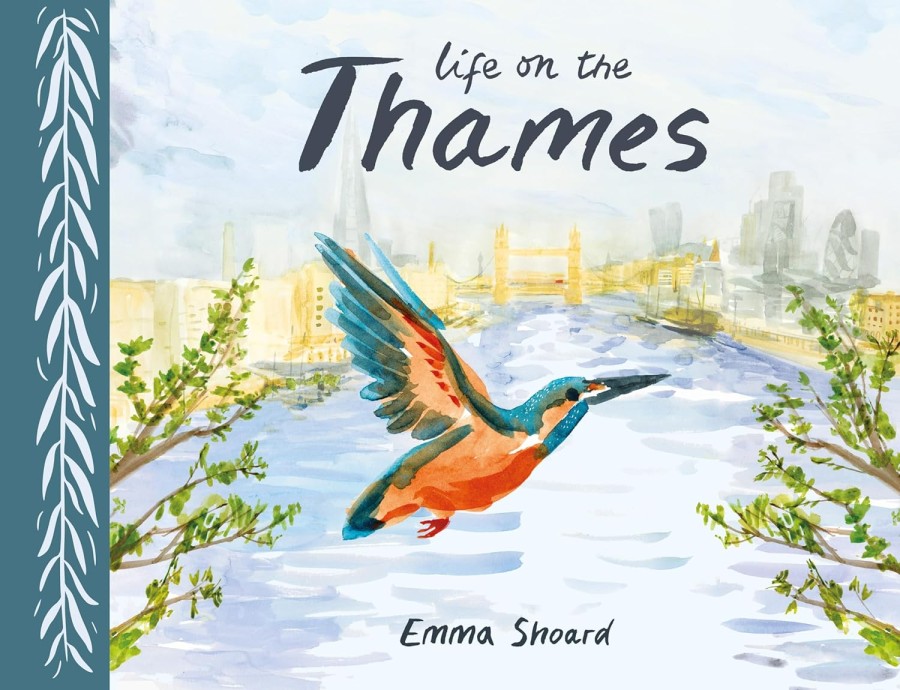

The Thames used to be so polluted, that Parliament would have to regularly close down due to the stench. Today it’s much cleaner with many mudlarking for history of its past (use tide times for safety, just like for the sea). Life on the Thames is an illustrated journey along a river that sustains a staggering number of birds, mammals and other creatures.

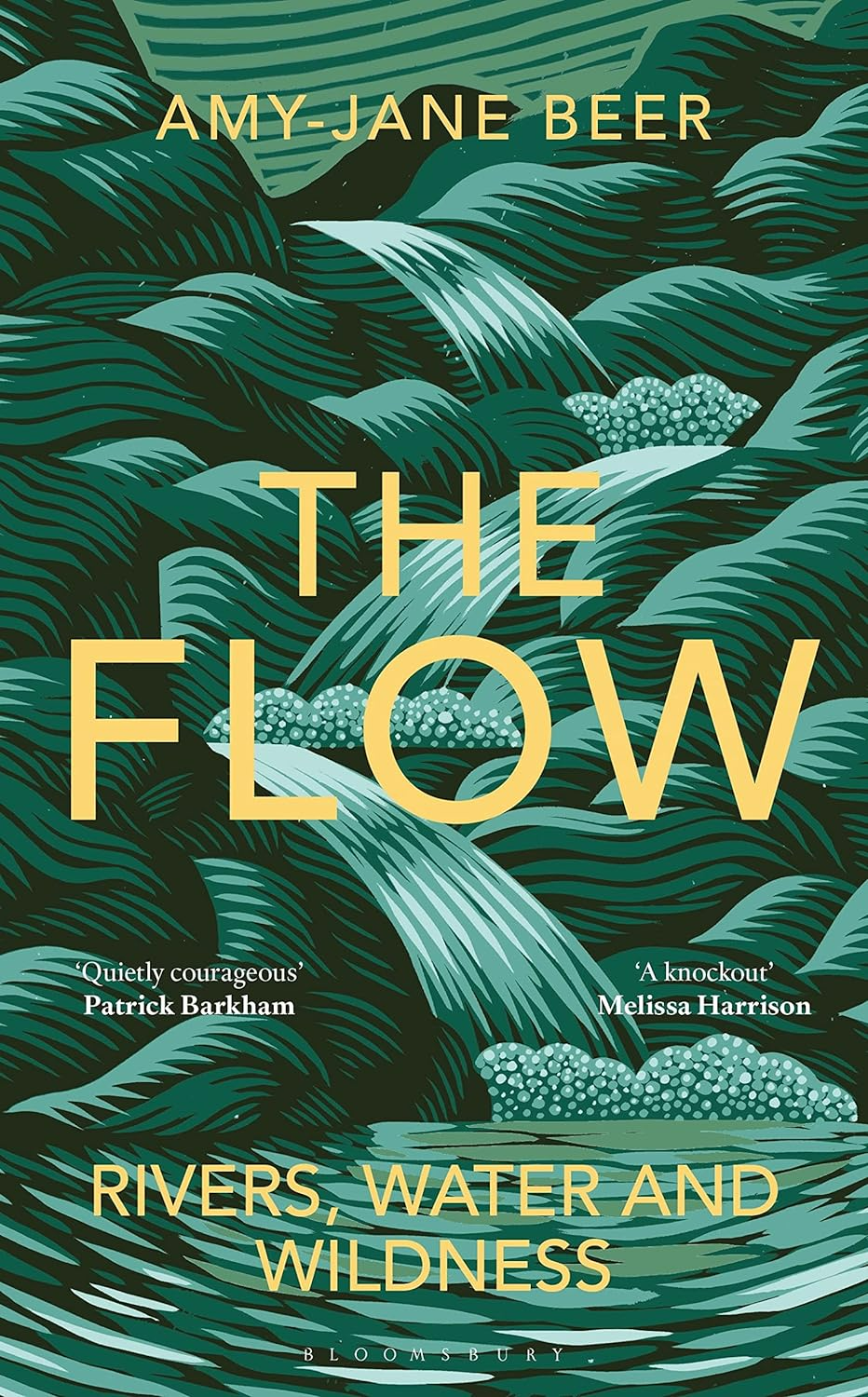

The Flow is a a writer’s journey along the rivers of England, taken after her beloved friend Kate set out with others to kayak the River Rawthey (Cumbria). But she never returned, and her death left her family and friends unmoored. From West Country torrents to Levels and Fens, from rocky Welsh canyons to the salmon highways of Scotland – through to the chalk rivers of the Yorkshire Wolds, Amy-Jane follows springs, streams and rivers to explore tributary themes of wildness and wonder, loss and healing, mythology and history.

Walking the Wharfe is by local boy Johno Ellison, who returns from living abroad to walk the entire length of the waterway where he grew up. Retracing the steps of Victorian writer Edmund Bogg, he begins in the Vale of York, walking upstream to find Victorian spa towns and rare red kites that have returned, thanks to conservation initiatives. He is seduced into wild swimming a chilly river (not the section notorious for reportedly drowning everyone who has ever tumbled into it). And seeks refuge in a candlelit pub, during a power blackout).

The River Wye was recently voted England’s favourite river. Rising in the mountains of Wales, it flows south for 150 miles to meet the River Severn, meandering through the Wye Valley (an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) from Hereford to Chepstow. Many local campaigners are working to protect the river, as pollution has decreased the quality of the water.